Yasmina Jaafar :

«You can't be free if you're not brave»

In her first book, journalist Yasmina Jaafar pays tribute to the African-American idols of the 1950s. Free and feisty, they express deeply political views.

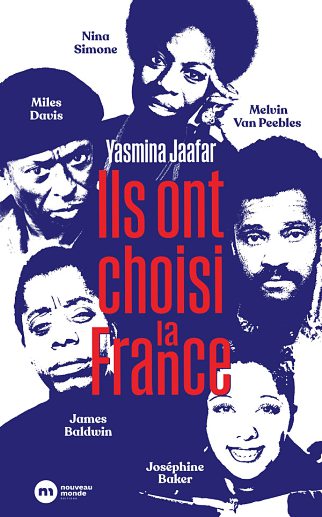

Outspoken, sincere and committed, Yasmina Jaafar, producer, journalist and founder of the website La Ruche Media, speaks and writes from the heart. Her first book, Ils Ont Choisi la France, retraces the journey of five African-American artists who chose France in the 20th century to make their voices heard and defend their values. Their main point in common: being born black in a country where segregation prevented them from realising their full potential. A few days after Donald Trump's inauguration in the United States, and at a time when many American artists have announced their intention to leave the country during his term of office, would James Baldwin, Miles Davis, Josephine Baker, Melvin Van Peebles and Nina Simone still choose France? Would they still enjoy the freedom that allowed them to be considered artists above all else? This passionate and well-researched work examines history, current affairs and humanity. Threats and hope. An encounter with a woman for whom identity, exile, universalism and peace are not empty words.

AM: What motivated you to write this book?

Yasmina Jaafar: The American writer James Baldwin. This civil rights activist, who broached the issue of sexual freedom long before the LGBT movements, said: ‘I am not a negro, I am a man.’ He also said that if we continued to complain, we would be partly responsible for our own misfortune. When I read this in Petit Traité du Racisme en Amérique, written by Dany Laferrière (Grasset, 2023), I immediately wanted to work on this man. I couldn't understand how France, the country I love so much, could have forgotten him. So I had to tell his story. To reach a wider audience with my book, I decided to also talk about two friends I love, Nina Simone and Miles Davis. And also about Melvin Van Peebles, because I love films. Lastly, Josephine Baker, the sixth woman to be inducted into the Pantheon. But the basis of my book is James Baldwin, who tells us to be careful, to take care of who we are and of our identity. The reason I love this man so much is because he is constantly writing the same book, without ever repeating himself: he persists.

Who is your book aimed at?

I would like it to reach all young people aged 16 to 25, so that they can look at themselves in the mirror and know that they are on the same journey. To appeal to parents, I initially designed the cover like a movie poster; I wanted this book to be a film. However, when I talked about this on TV, I was told that Raoul Peck had already done this with I Am Not Your Negro (2016), even though this documentary, which is based on Baldwin's unfinished book, is about Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King. It has nothing to do with James's life. I wasn't going to argue. I've been working in television for thirty years and I know exactly how it works. So I found a roundabout way. My book will be adapted for the cinema and released in the United States.

Why did you focus on the post-war years?

Because I started with Baldwin. He made me realise that, in the 1950s, there was a French schizophrenia. America was praised to high heaven because it had just got us out from under Hitler. At the same time, there was the colonialism issue. France no longer knew where it stood with its foreigners and the way it looked at the children of colonised people. It was having problems with identity claims and tends to confuse its history with American history. The same goes for the issue of racism. Slavery, which lasted four hundred years, originated in a fundamentally and systematically racist country, whereas France is not a systematically racist country. That is why I oppose certain current arguments that confuse histories and narratives. The national narrative does not interest me, because it summons up history, and if we do not know it, if we confuse it with other histories, we lose our way.

You write: ‘Colonisation is not slavery.’ Could you expand on that?

Colonisation is a despicable act that reduces and diminishes one human being in relation to another. It is a period in which a state takes over a foreign land in order to exploit its natural and human resources. An economic way of growing and existing. But there is a difference in political method and objective compared to slavery. I would first like to point out that the word ‘slave’ comes from the medieval Latin sclavus, another form of slavus (Slav), because during the early Middle Ages, many Slavs, i.e. white people, were enslaved by the Germans and Byzantines. It was not until 1650, with the slave trade, that the word ‘black’ came to refer not only to an African person or a skin colour, but also to a slave. Slavery is a system of radical domination, which reduces human beings to immediate financial gain, deprives them of their freedom, chains them, kills them, beats them, annihilates them, exterminates them. The aim is not the same as that of colonisation. Even if, of course, both methods amount to crimes against humanity.

Seventy-five years after the fifties, which is when the African-American celebrities featured in your book arrived in Paris, how do you see the United States and France?

We can't say that the United States is going backwards, when France seems to be regressing somewhat. America has to be seen in its complexity. Its people are resilient and allowed Trump back into office because they need financial security and to maintain a kind of supremacy. They have become bogged down in wars that have cost them dearly, and this particular president is not a warmonger. They voted for him for reasons other than those we might imagine. As for France, it has beautiful fundamental values of liberty, equality, secularism... but the French are forgetting those values because American soft power has Americanised them. So we are going backwards. And it's not a fad. I think there is a paradigm shift. So I wrote this book because I wanted to tell kids, ‘Stop thinking you're Michael Jackson.’ I love American music and soft power, but I'm not American, I'm French. And just because I say I'm French doesn't mean I'm going to vote for Marine Le Pen. I want to reclaim the word nation, the word homeland, secularism. And when I, a Franco-Moroccan, hear Jordan Bardella say that dual nationals would be banned from a number of things, I speak out. I am fundamentally Madame de Staël. Combative. They'll never take that away from me.

What does Trump's re-election tell us?

We've changed worlds. Trump has a sense of strategy and economics, not necessarily of trade, but he's a show-off, a TV personality, someone who knows how to advertise and entertain. A master of slogans. We live in a time when thought is reduced to social media posts and punchlines. He's therefore a man of his time, not fashionable, but current. He represents what we are today, globally, worldwide, in the way we fail to respect ourselves, to take the time for anything. He's very clearly where he belongs. And then he joins forces, because he's smart, with people like Elon Musk. Because the logic is to create a Trump brand. This country is extraordinary. There are people who are constantly struggling and Trump is winning the battle of those who no longer want to struggle, because the problem is economic and money is needed. It doesn't matter whether people like him or not, they need to be able to live a normal life. When you have to pay 800 euros for the slightest medical procedure, I understand that you are desperate and that he becomes the man for the job.

How would you define racism?

I would say that it's a way of debasing others because you feel superior. It's really saying: «You're nothing, so I'm going to take over your life and your thoughts and reduce you to nothing.» And it is inherent in the human soul. I said so in my introduction. Racism will always exist, it was born with us and will die with us. We are all racists against someone, something, in any population. That's how it is. The 'other' is different, we don't want to feel inferior and we need to feel superior to reassure ourselves.

How is this fear of difference exploited?

The media and social media, which create silo thinking, are largely responsible. We think in very specific terms with our ‘friends’, who emphasise issues of racial identity rather than talking about real economic problems. What I am trying to say in this book, and in the next one, is that if we do not solve the problem of education, school and money, we will find ourselves with racism, which targets people's origins, and xenophobia, which refers to hatred or rejection of foreigners, becoming increasingly important. And this will be linked to the fear of not having enough to eat. Playing on fears through the media, through politics... That's how you create racism instead of focusing on the economy.

All of this is not very optimistic...

I am, by nature, a realist and I think it's better to tackle things head on. Everyone has their own way of doing things. I wasn't born to write books: I was born in the 93rd district and grew up in the 20th. Very early on, I said that I wanted to be on TV and one of my teachers said to me: ‘You have three disadvantages: you're black, fat and Arab. So you won't be on TV.’ I persevered and did it anyway. It's my way of contributing, of not giving in to pessimism or defeatism. So I try to pick up my pen and talk to people. That means I still have a little faith. Will there be a turnaround? Will we become a liberal society? Will Voltaire's country yield to the far right? There are still lots of little things that tell me that, perhaps, we could escape the worst.

In the chapter about the filmmaker Melvin Van Peebles, you mention one of his films, Watermelon Man, in which a deeply racist white man wakes up to find himself black...

We have somewhat forgotten this pioneer of Blaxploitation [a film genre of the 1970s, the majority of whose films focus on African-Americans, Ed.], who died in 2021. This temperamental, subversive man, who learned French with Cabu [French comic strip artist and caricaturist, Ed], decided to turn the tables at a time when there were no Denzel Washingtons or Will Smiths. He was a soft-hearted rogue, a troublemaker who dared to portray a very powerful political act in his film, which says that when you are white, you are just as enslaved by your madness as a black person. You are therefore the mirror of this. So why do you need a black person? Perhaps because you are not completely aware of who you are or sufficiently reassured by who you are. In the film, there is this sequence where the protagonist, who has become black, takes a bath in milk and rubs his skin because he wants to become white again. His wife, a total, empty-headed racist, leaves him, forgetting that the man hasn't changed: he's still the same racist husband, because he wants to erase his blackness. Van Peebles forces the man to face his stupidity. In his Dictionary of Received Ideas, Gustave Flaubert, whom I really like, also enjoys exposing the misconceptions, stereotypes and ignorance that inhabit the bourgeois, revealing their true nature: stupidity. It's like when we reject others: who are we angry with when we bark at someone all day long? Ourselves. It's essential to be able to tell yourself in two minutes that if the other person is a problem, they're just a stepping stone for all the unease you feel. That's what the film says. All kids should see it, schools should show it again, multimedia libraries should stock it. We need to shout from the rooftops that Melvin Van Peebles has hoodwinked Hollywood like no one else before him. It's extraordinary. We need that today, even more than yesterday, because we keep comparing ourselves and it's incredibly unhealthy.

Which work or achievement would you choose to illustrate the commitment of the four other personalities in your book?

For Baldwin, it would be La Chambre de Giovanni, a tormented passion that ends in tragedy, and La Prochaine Fois, le feu, in which the author looks back on his childhood and early adult life as a person facing triple discrimination – black, homosexual and poor. Two books written in 1956 and 1963. For Miles Davis, I would say Ascenseur pour l’échafaud by Louis Malle, in which the soundtrack plays a crucial role. He wasn't even thirty when he composed his film score, by watching twenty to thirty second excerpts. His improvisations were recorded in barely three hours. What interests me is the profound feeling of freedom he experiences when he arrives in France, which perhaps unleashes his genius. As if he became a different man in the space of an instant, arriving in Paris from a self-centred America, where he immediately understands, finds love, and above all feels he has the right to be an artist above everything else. And that changed the whole world of jazz. Josephine Baker arrived in France earlier. It was 1920, she was on a cruise ship and she met Louis Armstrong. I think she meant what she said when, dressed in her Free France uniform, she gave her speech on 28 August 1963 alongside Martin Luther King during the great civil rights march in Washington. I include the full speech in my book. The rest of the time? I'm not sure, she was a strange and complex woman. And Nina Simone! She makes me cry. She is completely misunderstood. She went from a kind of tormented, irritated Malcolm X in her concerts, to wanting to kill white people, to: ‘Enough is enough, stop complaining.’ Undiagnosed bipolar, so frustrated at not becoming the pianist she wanted to become - it killed her, in fact - this woman is incredible. No one says it, but Nina Simone is not a singer. I prefer her piano music, and I'm happy with that. In fact, what moves us in her voice is that she sings with anger.

Who are your role models?

Madame de Staël is still top of the list. This avant-garde and rather complex Swiss woman of letters was perpetually in love, excessively possessive, with tumultuous affairs and desperate romances. At the same time, she demonstrated formidable political acumen. Freedom in all its forms was one of her crusades. She and Madame Récamier were opposed to Napoleon, who I am not a fan of because he loved himself too much – I am more inclined towards Talleyrand, who preferred France to himself. These people make up my pantheon. Not forgetting Antonin Carême, the great chef of Napoleon's time! When he was six years old, his parents abandoned him because they had no money. He found himself on the street, where he worked as a kitchen boy, apprentice, pastry chef, etc. And became Carême, king of cooks. He invented everything: the vol-au-vent, pots and pans, the chef's hat, and brought culinary art to the attention of all the courts of Europe. My female and male role models all refused to accept determinism.

Nina Simone, whom you quote, says: ‘Freedom is a feeling. Freedom is no fear.’ In today's world, what is freedom?

Today, freedom is a luxury. But you can't ‘just’ be free, it doesn't mean anything, you can't do whatever you want. Freedom is what we grant ourselves in a specific, small area. To try to be a little happy all the time. Moments of happiness, just moments. It's the possibility of daring to express oneself and to decide for oneself. I don't want children: I'm not having any. I want to be rich: so what's the problem? I want to be famous: why not? But also why? And you have to accept all that. With courage. You can't be free if you're not brave. Brave in everyday life, in your little life, like that. And you have to know how to say no.

Would James, Miles, Joséphine, Melvin and Nina have chosen France in 2025?

Yes, yes and yes. But I don't want to answer for them, it would be rude and presumptuous. The France they have chosen is the one I love, the one we all love. It is the France of the terroir, of conversation, of beauty. It is the France of the 18th century, of D'Alembert and Diderot, constitutive of who the French are. It is the land of intellectuals and open-mindedness, which allowed the French, with L'Encyclopédie, to learn more about life and about themselves. We are still that country in relation to the madness in which these African-American artists were born. We must not forget that.