That was BBY

(1928-2021)

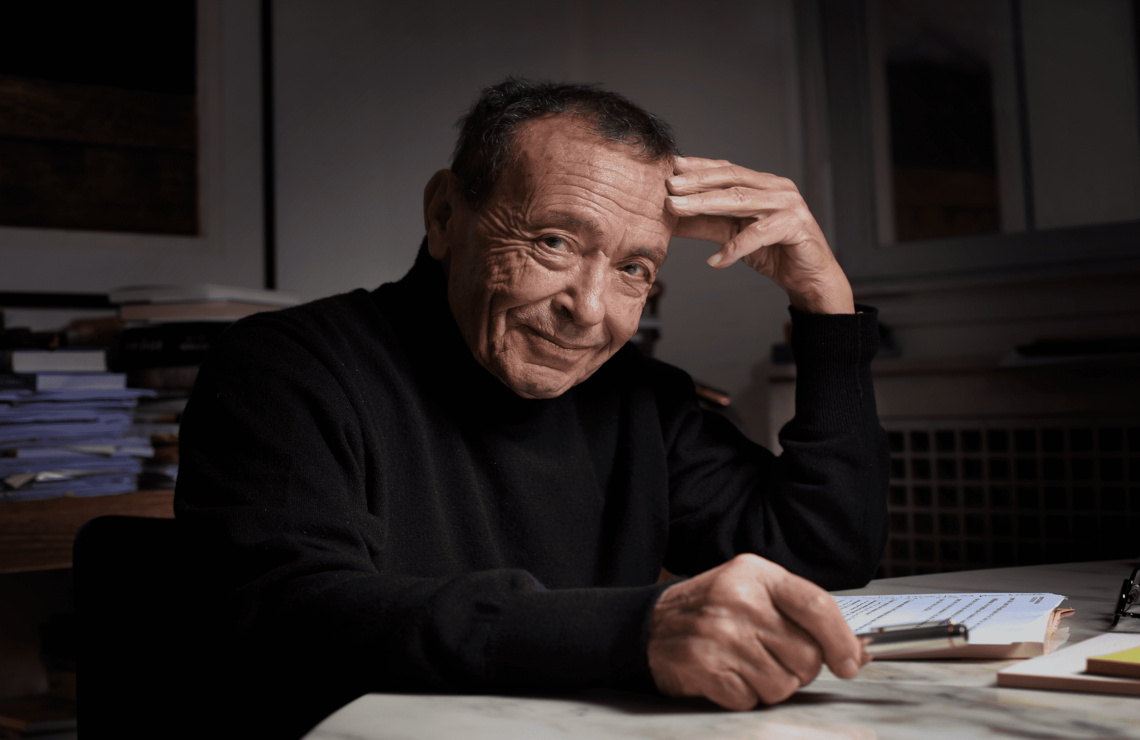

Bechir Ben Yahmed left us three years ago. On 3 May, International Press Freedom Day, like a final salute. Here is our tribute to him, first published in Afrique Magazine in June 2021.

It was two days before his final departure, in his room at Lariboisière Hospital in Paris. I was at his bedside, beside the man who raised me, who made me a large part of what I am today, through his example, his career, his history, his influence, and even through our confrontations... Béchir Ben Yahmed was ill, stricken with Covid-19. He had been fighting bravely for over a month. But the doctors were longer very hopeful. BBY was lucid, as if on his feet. True to himself, seeking to be master of his destiny, captain of his soul (to quote a famous poem by William Ernest Henley). He wanted to be clear about the meaning of this struggle, about the ‘after’, about the ‘why’. “I'm not afraid,” he said. “I don't want to be dependent, I know that my life has been lived. I've done the best I could between where I started and where I am now.” He showed concern for my children and their education, and told me to do everything I could to protect them. Simple things that we hadn't often said to each other.

We talked about Africa, the great story of his life. I asked him which public figures had had the greatest impact on him over the years. He told me about Habib Bourguiba, the man who gave him his political education, who made him a short-lived Minister of Information at the age of 28. And indirectly a magazine publisher. The break would come one resignation later, when BBY, by then the founder of Afrique Action, wrote a hard-hitting editorial titled ‘Le Pouvoir Personnel’ (Personal Power), criticising the gradual establishment of Bourguiba’s absolutism. “Bourguiba,” said BBY, “had three major achievements that make him incontrovertible: independence, education for all and the emancipation of women.” It was tempting to do some quick psychoanalysis, to see Bourguiba as an idealised father figure. BBY rejected this idea. He only had one father, Si Amor, with whom he had a strong and complex relationship. BBY was, first and foremost, the man behind a great, rare, improbable, transformative, brilliant and, from any standpoint, probably unfeasible project: Jeune Afrique. An independent weekly covering the whole of Africa and embodying the ideals of independence. A magazine for an entire continent, barely emerged from colonialism, whose states seemed to have been drawn up on the corner of a table, with no real modern means of communication. He had to create the title, build the company, bring JA to life, surround himself with people, recruit and train them, develop JA, defend JA, sometimes against all odds, not lose it, not sell it – above all not sell it. Standing up to the most vicious and dangerous attacks, such as the repeated onslaughts (by the OAS, extreme right-wing groups, agents close to Gaddafi, etc.). To make it a respected publication despite the constraints of a continent with few resources and little advertising. To be skilful at navigating between different powers and interests. And every week, or almost every week, to write that famous editorial, ‘Ce Que Je Crois’ (What I Believe) that has most certainly left its mark on two or more generations of readers.Bourguiba was something else, he was the leader, the chief who galvanised them, who brought together these personalities who were already involved in the struggle for independence. The link was essentially political.

As we continued our discussion, BBY pondered: “There's obviously Léopold Sédar Senghor, a very important figure.” Senghor the writer? “Yes, but above all Senghor the politician, the man of power who knew how to be modest, who knew when to leave. Some heads of state called him a traitor at the time. Above all, he showed courage and lucidity.” He also talked to me about Alassane Ouattara, about the long friendship they shared for nearly forty years, with commitment on both sides: “Contrary to what his opponents say, he is one of the very few people who can hold Côte d'Ivoire together...” A pause. And just before I leave the room, speaking of himself: “People forget quickly, posterity is very fragile, presumptuous.” Another pause. “The world is changing, everything has become unpredictable, nothing will ever be the same again...”

Béchir Ben Yahmed passed away in the early hours of Monday, 3 May 2021. World Press Freedom Day... A beautiful and tragic coincidence. He was 93 years old. He had lived a full and complete life, the life of a man who wanted, above all, to be free. Founder of L'Action, and of Afrique Action, which became Jeune Afrique in 1960, owner and editor of the magazine for nearly half a century, and founder of La Revue, he was a committed African, a crusader for the freedom of peoples and the emancipation of the ‘South’, a demanding contributor to public debate since independence, and a clear-sighted observer of the world. BBY was a child of the century, born in Mahboubine, Djerba, in 1928, and a witness to the struggle for independence, the fall of colonialism and the difficult construction of these new worlds. Throughout these decades, he carried a distinctive, committed voice, an intelligent, uncompromising view of human affairs. He could see far ahead, but he himself was a man like any other, with his constraints, his limits and his innermost impulses.

Power intrigued and fascinated him and, in his own world, he practised it with talent and often ruthlessness. He imposed himself, mindful of the balance of power, the all-powerful head of his company. “Power is not given, it is taken”, he once told me by way of political education. He engaged in debates, conversations and conflicts with the most powerful people, unashamedly and skilfully. But he was also wary of hubris, arrogance and injustice. He saw himself as a true democrat, without ambiguity. “I can understand the need for authority in a developing country. But every year, democracy must grow by 10%. That's an imperative that every head of state must set themselves.”

However, what he wanted most of all was to be truly different. To stand out from the crowd. To be original, different from the others, the generation of independence activists who became ministers, senior civil servants, and even presidents. Although sometimes he certainly thought about it. Media boss was a good idea, the perfect fusion of all Béchir Ben Yahmed's personalities. And this new freshly independent Africa, was a great inspiration.

What emerges is the portrait of a ‘whole’, multi-tasking magazine owner... A boss who couldn't be categorised, with his journalistic flashes of brilliance, his epic and often excessive fits of rage. A boss anxious to construct and deconstruct, so as to rebuild differently. An entrepreneur perpetually on the move, in search of a new adventure, a new venture that would satisfy his ambition, his intellect, and no doubt his fear of stagnation. He was adept at uprooting himself. Always striving for more perspective, a different point of view, one of his favourite sayings was: “The essential is constantly threatened by the insignificant.” And yet often submerged in detail.

BBY could also be touchy, which didn't always make things easy. He attached a great deal of importance to etiquette, couldn't stand people not replying to a letter or a formal request, couldn't stand being ‘let down’ (although he was often very subjective about the definition of ‘let down’). He could sever ties abruptly, definitively, but he also had loyal friends, long-lasting, inseparable ties, despite differences and disagreements. His true friends know who they are, and there aren't many of them. His mentor in journalism and publishing, the man who probably showed him the way without realising it, was Hubert Beuve-Méry, the founder of Le Monde, whose editorials he would devour and whose analyses he shared, particularly on issues of decolonisation, North-South relations and French politics.

He saw himself first and foremost as a businessman who was risking his assets, his reputation and his family. Money was central to his struggle. “I've spent my life solving material problems.” More than once, his newspaper and his businesses teetered on the brink of ruin. And when panic swept through the ship, the captain always seemed relatively in control, able to hold the teams together, using his connections here and there, reassuring everyone in the end. And to those who criticised him for letting himself be ‘bought’ by this or that party, BBY replied firmly: “Compromises sometimes, but compromised – never.” JA remaBBY was a cautious man, a strategist, tenacious and skilful, but he could be charmed by a Rastignac (the name of a fictional character from Balzac's ‘La Comédie Humaine’, who uses his own wits and charm to get what he wants, Ed) or a smooth talker. BBY was, on more than one occasion, his own enemy. But he knew when to stop and make a U-turn. He knew how to put the brakes on before things went too far.

ined independent. No one could really dictate the weekly's editorial line. It was always balanced, in one way or another, and sometimes two journalists could defend two different views on the same country... But the price of this freedom could be particularly painful: distribution bans, advertising and contract cancellations, etc.

BBY could also be touchy, which didn't always make things easy. He attached a great deal of importance to etiquette, couldn't stand people not replying to a letter or a formal request, couldn't stand being ‘let down’ (although he was often very subjective about the definition of ‘let down’). He could sever ties abruptly, definitively, but he also had loyal friends, long-lasting, inseparable ties, despite differences and disagreements. His true friends know who they are, and there aren't many of them. His mentor in journalism and publishing, the man who probably showed him the way without realising it, was Hubert Beuve-Méry, the founder of Le Monde,whose editorials he would devour and whose analyses he shared, particularly on issues of decolonisation, North-South relations and French politics.

Beuve-Mery was a journalist, an editorial writer, a committed leftist, and an intellectual, but he was also a man of action, who had to build a daily newspaper, protect its independence, and defend it against attempts by political powers to neutralise it. BBY had a certain affection – bordering on admiration – for Pierre Mendès France, a man of principle, the architect of decolonisation in Tunisia and Morocco and of extracting France from the Vietnamese quagmire. He was close to Jean Daniel, a few years his senior, with whom he narrowly escaped being shot by the French army at Bizerte in July 1961. And because BBY, the leftist, the progressive, was never short on contradiction, he was also friends with Jacques Foccart, the embodiment of post-colonial Françafrique, the man with the networks and, it was said, known for what one of his collaborators, Philippe Gaillard, jokingly called the helicopter theory: “Often too high, often too low”. BBY had a genuine curiosity as a publisher, as a specialist in power and politics. And from this astonishing encounter was born a series of essential books, Foccart's memoirs and notebooks, with the help of Philippe Gaillard, co-published by Fayard and Jeune Afrique.

ARCHIVES JEUNE AFRIQUE-REA

BBY believed in hard work and, above all, perseverance, that steadfastness in striving towards the desired goal. “The world is populated by intelligent people who have failed”, he once wrote in one of his countless notes of personal reflection that mounted up on his desk in impressive piles, as if in a permanent and necessary exercise of introspection and hindsight. With BBY, perseverance and pragmatism always went hand in hand.

BBY was not an easy boss, I know that for a fact, as do both my brothers, Amir and Marwane. He was an all-powerful boss who was difficult to challenge or contradict, but he also believed in the virtues of teamwork, and had his editorials proofread by everyone. Those big editorial meetings could often prove trying, with hot or cold fits of anger, depending on the subject, and justified or unjustified criticism. But they were also a place of tremendous creativity, intense dialogue and a battle of ideas. BBY had his own opinion, but he wanted to hear the opinions of others. He exerted a formidable magnetic pull, attracting to Jeune Afrique a wide range of personalities, both talented and shady. He also brought in novices who knew nothing about the press, beginners whom he turned into journalists, young exiled opponents looking for a way to express themselves and take action (again...). It was the famous Benyahmedian theory of the swimming pool: “If you don't know how to swim, we’ll put you on the edge, push you in, and the good ones, the real ones, will manage in the end...”. Over the years, the publishing house has trained a multitude of talents. It's hard to name them all.

Sometimes these relationships ended badly, with noisy, brutal break-ups, but almost everyone has lasting memories of their time at JA, the feeling of having been part of a singular adventure with a singular boss. For BBY, there was a sort of ‘golden group’ of historical figures who contributed to making JA what it is today: Aldo de Silva, Sennen Andriamirado, Siradiou Diallo, François Soudan, Jean- Louis Gouraud, and his friend, the chartered accountant Moulay Hafid Amazirh. And his close family.

We cannot talk about BBY without talking about Danielle, his wife. And my mother. BBY without Danielle would certainly have been an entirely different story. The meeting between the attractive 40-year-old head of JA and the young widow of Mohsen Limam (my father, who died in a plane crash in November 1966) took place in Tunis, at a dinner with a close friend, banker Serge Guetta. Danielle and Béchir married in Rome in 1969. DBY became a real partner in the company's development, with the founding of Editions Jeune Afrique (later Editions du Jaguar), the first publication of the Historical Atlas of Africa, the Today country guides and a series of coffee-table books. All through the years, DBY has been the ‘PR’ interface, always there to sort out complex situations and safeguard relations between the various parties. She was also responsible for a large part of the company's development. In a way, she was his double; they were a true couple, partners in every facet of their lives. DBY was also one of the finest dinner party hosts in Paris (in their various successive homes) and in Tunis (at their home in Gammarth, by the sea).

Danielle Ben Yahmed was also the one who envisioned and launched Afrique Magazine in December 1983. It was a diversification project for Groupe Jeune Afrique, a desire to look at the continent in a different way. I started out there as a freelance writer (in the motoring and film sections), and was editor-in-chief on several occasions, progressively identifying with the title. And when, in late 2005, I left BBY as boss for good and Groupe Jeune Afrique as my employer, I negotiated to buy the monthly. BBY encouraged me: “Go ahead, try your luck, be true to yourself.”

BBY was all that. Paradoxically, it was also the desire to move beyond JA, to assert his own voice, his own writing, and his own analysis in the great theatre of the world. He was constantly striving to transcend his own intellectual and geographical boundaries. He wanted to prove to the world that a Tunisian, an Arab, an African could do as well as the ‘others’, despite a lack of resources. “I wanted to create a magazine that transcended borders, that would be known the world over”, he said without false modesty. It was this logic that led to his very temporary ‘disappearance’ from Jeune Afrique in favour of L'Intelligent. And it is above all the reasoning behind the last publication of his life, La Revue, which he wanted to turn into a sort of ‘international French-language New Yorker’ or a more literary Economist. It was a pretty tall order, perhaps because of a lack of resources. Either way, BBY had long since become his ‘own enterprise’, his own ‘brand’. He was known and recognised. He initiated dialogue on all sides, between Jews and Arabs, leaders and opponents, and rubbed shoulders with writers, singers, artists, bankers and entrepreneurs. And heads of state, without being seriously impressed, which was always impressive. Occasionally, he fell passionately in love with a personality, a candidate, and threw all his weight behind them, unabashedly, while explaining the reasons for his choice. He may not have succeeded entirely in producing the major news publication of his dreams, but he was a figure who counted, who was listened to, who shaped public debate.

Above all, BBY had ‘readers’, close or less close, who read him, readers everywhere, in the four corners of Africa and the world, whose political and public consciousness was moulded by his writing, his editorials, the covers of JA and La Revue. One of BBY's real talents was his ability to see beyond the immediacy of things. To ‘read’ through the din and the elation and the tragedy, to spot where the real lines of structure and fracture lay. He didn't relate to emotion, which he probably saw as a weakness. He always sought to be rational and reasoned. Of course, subjectivity was always hovering on the sidelines, but his strength lay in his eye for the essential, his ability to decipher, without pathos, the course of Africa and the world.

These countless readers, of all ages and from all walks of life, also considered themselves – and still do – his friends, ‘reader-friends’ as it were. They were proud to be able to count on someone of his stature, to see one of their own recognised as a great media boss who had transcended his limits. And who stood tall at centre stage. From the late 2000s, BBY gradually handed over Jeune Afrique to his children Amir and Marwane, with the support of François Soudan. Legend has it that he didn't try to cling on, but he did want to control every stage of the transition as best he could. And he absolutely did not want to be on holiday, by the sea, doing nothing. He hated the idea of retirement. La Revue gave him the opportunity to keep working, to stay active, to maintain this essential component of his existence. He put together a small team in a wing of the offices at Porte d'Auteuil and, as he had done all his life, he fought to keep his project alive. And every day, despite the progressive weight of the years, he was the first one in the office, at 57bis, in the early hours of the morning, bright eyed and with (almost) a bounce in his step. He had also embarked on writing his memoirs, an account of his life that I'm sure we'll be talking about in future. A very complex process, in which I myself was largely involved, before being excluded. BBY wanted to tell his story, to explain, to bear witness, but his modesty and his complex relationship with emotion often held him back. And the density of his life, all those people he met, the sheer number of events he had lived through, made it particularly difficult to piece it all together.

For several months, BBY had been growing weary. This man, who needed to be on the go, found himself slowing down. He didn't want to be dependent. He didn't want to be weak. He needed prospects, and prospects seemed to be dwindling, shrinking. The Covid-19 pandemic arrived. Travel ground to a halt, and dinners, meetings and discussions were dramatically cut back. Jeune Afrique went from being a weekly to a monthly, buoyed by a stronger digital offering. It was the end of an era, if not the birth of a new one. BBY didn't always wear a mask, and was in no hurry to be vaccinated. Some may see that as a provocation. But it was also his way of refusing to change his life, his approach to life, before turning the last page.

|

Ce Que Je Crois BBY will have written more than 3,000 'Ce Que Je Crois ' (What I Believe), the emblematic editorial published every week or so, except in the event of force majeure and during the short summer break. The editorial is BBY's preferred form of journalism, where he can really exercise his talent for analysis in complete freedom. That's what he thinks, he puts his name to it, and not necessarily that of his magazine (JA or La Revue). For BBY, the editorial started 48 hours before the deadline, he had to choose his topic and gather his ideas. And documentation. Maybe make a phone call or two. And then he had to write, by hand, on those famous personalised notepads, in that famous green ink he used throughout his life. BBY would write, rewrite, strike through, set himself a time limit, have the copy typed, pass it around between three or four people, discuss corrections, opinions and contradictions. And then he delivered his final version. He wasn't afraid to be cutting, iconoclastic, to go against the grain, to acknowledge his subjectivity. And above all, there's that formidable eclecticism, that boundless curiosity that can take him down any path, be it science, geopolitics, demography, religion, power... |

|

A Tunisian in France Born in 1928, BBY lived through colonisation, ‘white’ rule and the near-apartheid that prevailed in Tunisia between ‘natives’ and ‘residents’. Those years left deep wounds. Some memories stuck with him, like the fact that even at the Tunis post office, all the tellers were white. That you could be assaulted on a bus near Tunis because you were a young Arab (true story). After much hesitation, BBY became French in 1994. “It was ridiculous. I'd arrive at the airport in Paris with my wife and children: they'd go to the right, and I’d have to go to the left, which could take an hour or more. And then there was the ordeal of getting a residence permit, with surly and often racist officials. And sometimes I'd have to go to Switzerland or Belgium from one day to the next, it was hellish, visas, etc.” As he says himself, BBY loved and spoke French, his means of expression, he had a company based in France, he had French people working for him, he felt a friendship for the country, but he didn't claim its identity. He became French by passport. But he always felt first and foremost Tunisian. To the very end. He went to Tunisia regularly, and maintained many contacts in all walks of life. He had a house there, and the historic offices of Jeune Afrique are still located in Tunis. For those who took part in the fight for independence, their hard-won nationality is a cardinal point, a source of pride. |