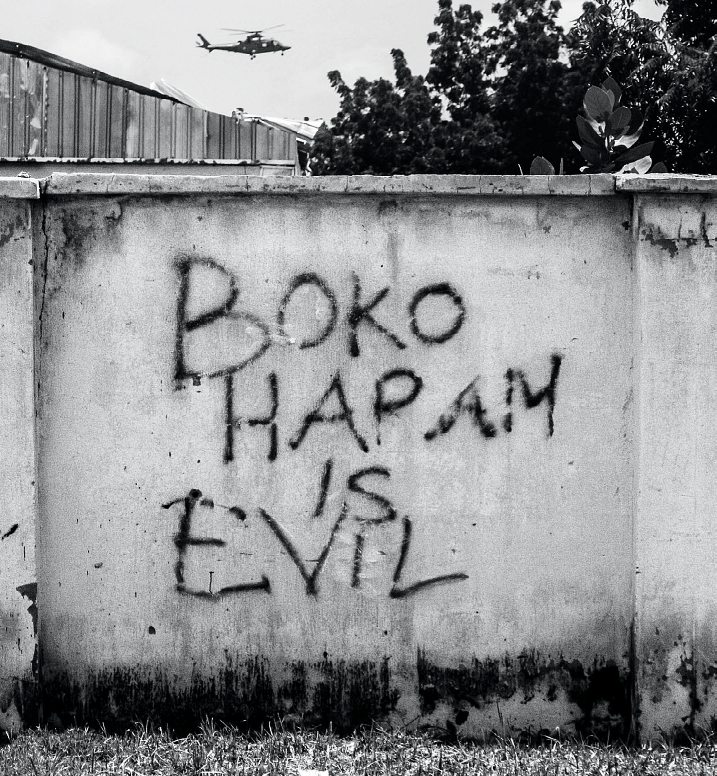

Security, the northern challenge

Northern Nigeria has been ravaged by violence for nearly fifteen years. In the North-East, social and economic life is returning following the military's recapture of territories in Borno State that had hitherto been infiltrated by members of Boko Haram and ISWAP. However, in the North-West, criminal groups are flourishing, driving civilians from their homes.

Slowly, Mai Aji Kolo, in his forties, pushes a rusty metal cart along the street leading to his home, taking the time to say hello to every neighbour he meets along the way. In this housing estate in Auno, a few dozen kilometres west of Maiduguri, the capital of Borno State, everyone is a former internally displaced person who spent several years living in the overcrowded conditions of humanitarian camps.

Like all his neighbours, Mai Aji was given the key to a two-room house free of charge. In November 2022, without hesitation, this farmer signed the documents formalising his return to a ‘normal’ life for him, his wife and their seven children. “I'm serene,” explains Mai Aji as he steps into his yard, “because every time I leave my house and come back, I find my family safe and sound. The community is also living in peace now. We are no longer threatened by Boko Haram.”

After putting his life on hold, shunted around with his family to various humanitarian camps in Maiduguri, this farmer can at last feel happy again. Like 160,000 former displaced persons, Mai Aji and his wife are the beneficiaries of a rehousing programme introduced by the Governor of Borno State, Babagana Umara Zulum. In 2020, when Nigeria was still struggling with the Covid-19 pandemic, Zulum travelled extensively to see for himself the progress made in terms of security in the main towns of Borno State which, until just six years earlier, had been under Boko Haram occupation. These towns are gradually being released from Boko Haram's stranglehold thanks to the combined efforts of the Nigerian army, organised around military ‘supercamps’ comprising several battalions, and its allies in the Multinational Joint Task Force (Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Benin).

True to his election promises, Governor Zulum committed himself to closing all the camps for displaced people in his capital, Maiduguri. He began by continuing with the housing reconstruction policy initiated by his predecessor Kashim Shettima, the country's current vice-president, before organising the first resettlement of families in their original communities. In many cases, Governor Zulum has personally accompanied these repatriations, to the astonishment of numerous humanitarian organisations, taken by surprise. “Before the Boko Haram insurrection,” explained the governor at the time, “Borno was a key state for agriculture. I want these farmers and fishermen, who can no longer contribute to the territory's economy, to return to their communities of origin to resume their activities.” Security around the returnees is being stepped up with the formation of agro rangers, attached to the Security and Civil Defence Corps: these volunteer militiamen in rural areas are tasked with protecting communities while they cultivate their fields. Ultimately, the aim is to take over from the Nigerian army, which does not have a mandate to remain indefinitely in areas considered free of Boko Haram.

Now, four years later, the effective closure of the 22 camps has changed the face and atmosphere of Maiduguri. Its village districts are changing, even if the vast majority of the inhabitants still live below the poverty line. There were a few signs that this transformation was beginning: the opening of several air links, breaking Borno's capital out of its isolation. And, above all, the unprecedented emergence of five-star hotels, to attract and retain a national and even international business clientele, as well as numerous property developments.

Shareef Hamza, sales manager of a cement merchant, is both a participant and an observer of this new era. The thirty-something explains: “From now on, we can put convoys on the road without fear, with each lorry carrying between two and three million naira worth of goods. Confidence has been restored. Not quite like before, when Maiduguri was an essential hub for wholesalers from Chad, south-east Niger and Cameroon. But let's just say that we have recovered 60% of our commercial strength.” The restoration of security and Governor Zulum's determination have served as accelerators. But for Hamza Suleiman, a security expert with Zagazola, the role of civilian volunteers in the war against the terrorist group is not adequately recognised: “Without these militiamen, the Nigerian army would never have succeeded. In all the counter-insurgency operations in North-East Nigeria, these men have been essential, and still are, in identifying members of Boko Haram.”

Threats and ransom demands in the North West

During the same period, in Nigeria’s North West region, another hotbed of insecurity erupted. At virtually the same time as Boko Haram began wreaking havoc in Borno. Initially the insecurity was low-intensity, with cycles of attacks and reprisals in small rural communities in Zamfara State. But then, over the past five years, the violence began to spill over into neighbouring states (Sokoto, Kebbi, Katsina and Kaduna). These are criminal groups engaged in mass kidnappings for ransom, armed robbery, cattle rustling, rape and other sexual violence, and looting of farms and mines.

After two weeks in hospital with her baby, this mother, barely twenty years old, has just obtained permission to return to her hamlet on the outskirts of Batsari – a town on the edge of the Rugu forest, a strip of cross-border vegetation stretching for almost 220 km between Niger and part of Katsina State in Nigeria. From this strip of woods, hills and caves, criminal groups terrorise the populations of Katsina, Zamfara and Kaduna states. So Mariam prefers to wait until the early hours of the morning before travelling. “We live in constant fear of bandits,” says the young mother. “They try to take our money, and if we don't have any, they kill us. I used public transport to travel here and we managed to get as far as Katsina. A military fighter jet was flying low overhead. It made it easier for us to get here. We weren't worried about the bandits. But sometimes they attack, so we have to run into the bush to hide.” Mariam, her four children and her husband are unable to move away from their hamlet due to a lack of funds. But, most importantly, they don't have the connections to try to move into Batsari itself and build a new life in urban safety.

However, this family is still able to access the plot of land they farm. Together with a dozen or so neighbours, they were able to scrape together the 200,000 naira (around 112 euros) demanded by the bandits raiding their area. Since 2014, between 500,000 and 700,000 people in North-West Nigeria have been driven off their land because of insecurity. The federal government has not yet enacted an emergency plan to respond to this humanitarian crisis. The bandits are particularly violent, and have no hesitation in killing their captives when ransoms are not paid. Kidnappings are not only an emotional burden for families; they also have a lasting economic impact on households in the North West, which, statistically, are already among the poorest in Nigeria.

Choosing to leave... or not

Since 2019, over 94,000 Nigerians have taken refuge in the Maradi region of Niger, relying on their family connections, due to the outbreak of violence in the North West of their country. Mariam's husband also considered taking his family across the border. But due to his wife's reluctance, he has given up on the exodus for the time being. ‘Our children are too young’, explains Mariam. “Besides, we can't just abandon our land. It's true that it's tough travelling on paths and roads where you constantly risk encountering these bandits. But I’m from Batsari. And I can't see myself living anywhere else...”