Rwanda

Resurrection under an iron fist

In April 1994, the ‘land of a thousand hills’ was plunged into bloodshed. This year marks the 30th anniversary of the Tutsi genocide. Despite this trauma, the nation has risen again under the strong leadership of Paul Kagame. With an innovative economy and real international soft power. At the price, however, of authoritarianism and growing tensions with its neighbours.

On the 7th of April, Rwanda commemorated the 30th anniversary of the Tutsi genocide. During that dark year of 1994, in the 100 days following the assassination of President Habyarimana on 6 April and the victory of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) on 17 July, Hutu extremists exterminated between 800,000 and a million Tutsis and tens of thousands of Hutu opponents. At the Kigali Genocide Memorial, where some 250,000 victims are buried, Paul Kagame lit, as he does every year, the flame of remembrance and delivered a speech celebrating the resilience of the Rwandan nation and the road it has travelled, as well as the efforts still to needed to ensure that the land of a thousand hills, survivor of the hell of genocide and ethnic hatred, rises ever higher, goes ever further. The President's guiding principle is: “Work hard until it hurts, because poverty hurts even more.” This aphorism is both liberal and Nietzschean, which sums up the ethos of the man who has been a warrior monk at the head of the Great Lakes start-up nation for nearly 30 years and who, at the age of 66, makes no secret of his desire to stay in power forever.

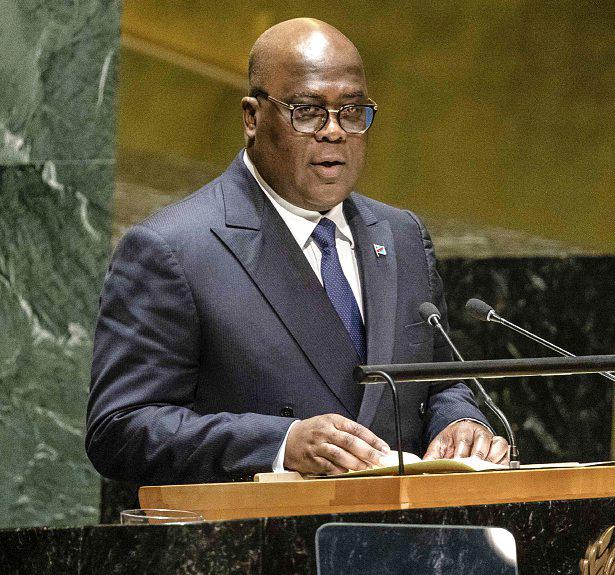

Many of the continent's heads of state were expected in Kigali on 7 April. Only two were not invited: president of the Democratic Republic of Congo, Félix Tshisekedi, because of tensions between the two nations, and Burundi’s President General Évariste Ndayishimiye. Kagame accuses Ndayishimiye, a former leader of the Hutu Forces for the Defence of Democracy (FDD), of supporting the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR) in the DRC, which yearn for Hutu supremacy and are sworn enemies of the RPF. Despite the recent warming of diplomatic relations between Kigali and Kampala, Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni, Kagame's former mentor, was represented by his vice-president, Jessica Alupo. France, meanwhile, was represented by its Minister of Foreign Affairs, Stéphane Séjourné, although French President Emmanuel Macron made a historic visit to Rwanda in May 2021, under the seal of reconciliation. During the commemorations in 2004 and 2014, Paul Kagame was quick to criticise the deplorable attitude of the Élysée Palace before and during the genocide. “The facts are stubborn”, he insisted during the commemorations in April 2014, which were held in French a language that the Rwandan president doesn't speak, having grown up in exile in Uganda. Since then, Paris has acknowledged “serious errors of assessment” in the Rwandan tragedy, but has never apologised. At the head of a France that he, too, aspires to transform into a start-up nation, “Emmanuel Macron is under Paul Kagame's icy spell”, explained Antoine Glaser, co-author (with Pascal Airault) of ‘Le Piège Africain de Macron’ (Fayard, 2023), to Afrique Magazine. The French President “has a fascination for the rare efficiency” of his Rwandan counterpart, believing that the latter has “a ripple effect throughout the region”. This efficiency was summed up by former Canadian General Roméo Dallaire during his recent visit to Rwanda, when he compared the capital to “an African Singapore”. As former head of the Blue Helmets in Kigali in 1994, he was able to gauge just how far the nation has come in three decades: “It's a job that I consider to be exceptionally well managed, by a hand firm, yes but with an ambition to really create a modern country,” the retired soldier told Radio Canada.

CLEAN CAPITAL AND COMPULSORY CLEANING

Kigali is undoubtedly the cleanest capital on the continent, thanks, especially, to the total ban on plastic bags introduced in 2006. The authorities are now tackling the issue of plastic bottles. A drastic measure, but a salutary one: a million bottles are sold around the world every second, but only 10 to 15% are recycled, the remainder often ending up in waterways, which they transform into cesspools where only mosquitoes thrive. In Rwanda, bags are therefore replaced by plant fibre baskets made by village communities and often by widows who survived the genocide. This meticulous urban cleanliness is maintained by the citizens themselves, who are requisitioned every last Saturday of the month for umuganda, compulsory community work, on pain of a fine. Gleaming Kigali is also a highly connected capital, with a well-developed fibre optic network and where the Internet has been available on buses (soon to be all electric) for a decade now. Rwanda is also a drone pioneer; the authorities were quick to recognise the potential benefits of these strange flying machines in the country's steep hills. Since 2016, these aircraft have been making emergency deliveries of blood and medicines to isolated clinics. The country also has a well-established telehealth system: since the 2000s, each village has a ‘community agent’ who reports health problems to the emergency services by text message. In October 2023, the Rwandan authorities and the Japanese bank SoftBank announced a world first: the successful testing of 5G connectivity from the stratosphere, via a high-altitude solar platform! The Great Lakes country's thirst for technological innovation seems unquenchable.

During the 2010-2020 period, Rwanda recorded the strongest growth in East Africa, with an annual average of 7.2%, thanks in particular to substantial public investment. After the 2020 slowdown due to the pandemic, GDP grew by 10.9% in 2021 and 6.8% in 2022. Rwanda attracted a record $3.7 billion in foreign direct investment (FDI) in 2021: ranked second in Africa (after Mauritius) on the Doing Business index, it is renowned for its business-friendly environment, thanks to its stability, security, low level of corruption and legislative framework. And it has the rare advantage of being both French- and English-speaking, following the return to the country in 1994 of Tutsi exiles who had taken refuge in English-speaking Uganda. There is one downside, however: legislation is changing so fast that the public investment bank Bpifrance is advising foreign companies to seek legal advice, at the risk of inadvertently breaking a law and being expelled from the country!

The poverty rate fell from 59% in 2000 to 38% in 2017, and life expectancy has increased by 20 years. With a still predominant agricultural sector (55% of jobs and 25% of GDP) and a worrying rural overpopulation (400 inhabitants per km2 compared with an average of 26 in sub-Saharan Africa), Rwanda is seeking to develop jobs in services. The country is banking on tourism, following the example of its neighbour Tanzania. An inclusive policy involving rural communities in the protection of the great primates has almost doubled the mountain gorilla population in 10 years, from 680 to 1,063 animals between 2008 and 2018 (the last poaching incident was more than 20 years ago). By emblazoning the shirts of Arsenal (2018) and Paris Saint-Germain (2019) footballers with the ‘Visit Rwanda’ logo, Kagame (an Arsenal fan) raised his country's profile amongst the European public. Rwanda drew 1.7 million visitors in 2019 and, once the impact of the Covid pandemic had been mitigated, 1.1 million in 2022, slightly fewer than neighbouring Tanzania (1.45 million), which boasts national parks and beaches. Quite a feat for a tiny country (26,300 km², an eighth of the size of Senegal), landlocked in the conflict-ridden Great Lakes region, where many Westerners had previously only seen the nightmarish images of genocide! Since 2012, Rwanda has also established itself, like Cape Town, as a conference hub, with an increasing number of MICE (Meetings, Incentives, Conferences, Events and Exhibitions), i.e. international conferences and trade fairs, attracting business tourism with high purchasing power. While Kigali was the first African city to host the FIFA Congress in 2023, the capital has also just launched Innovation City, its platform for hosting innovative companies. And next year, the country will host the 2025 UCI Road World Cycling Championships. In terms of soft power, Kagame, although an English-speaker, managed to get former foreign minister Louise Mushikiwabo elected head of the Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie (OIF) in 2018. He himself chaired the African Union (2018-2019) and the East African Community (2018-2021). The Rwandan contingent is also heavily involved in peacekeeping operations, notably in the Central African Republic, South Sudan and Haiti. Two years ago, the country also signed a controversial agreement with the United Kingdom, enabling the British to deport migrants who had entered the country illegally to Rwanda. The British Supreme Court invalidated the agreement, but the British and Rwandan governments are persisting. However, it is hard to see what Rwanda would gain from such a deal, apart from getting itself talked about on the international stage.

RESTORING ITS IMAGE

With every innovation, every publicity stunt, every media success, the image the country inherited in 1994 – that of a cursed land, a land of blood, hatred and cruelty – fades a little more, while another image takes its place: that of an innovative, efficient, stable and reliable nation, where investment is possible. “They [the international community] called us a small failed state. But we refused to fail, refused to be small,” Kagame told the country's young people in 2016. “Rwanda has changed for good and forever. We made three choices: We will always want to stay together, we will always be accountable to ourselves first, and we are not going to stop thinking big.” Few nations have seen their international image change so positively in such a short space of time. Dare we draw a comparison with post-1945 Germany: after World War II and the Holocaust, the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) achieved the feat of becoming not only Europe's leading economy, but also an exemplary democracy. The difference between Rwanda and West Germany obviously lies in political openness, with the Kagame system being as effective as it is authoritarian. “Paul Kagame is someone who leaves no one indifferent,” explains Antoine Glaser. “There are no other heads of state like him in Africa. It is not impossible that Macron fears Kagame, as is already the case with most African presidents.” In an interview given to our colleagues at Jeune Afrique on 14 March, the Rwandan head of state was downright threatening towards his Congolese and Burundian counterparts: “Tshisekedi is capable of anything, except measuring the consequences of what he says”, he asserted. As for the Burundian president, he accused him of “lying” and supporting his sworn enemies, the Hutu rebels of the FDLR. In his view, his two neighbours were encouraging “primitive politics based on ethnicity”. Paul Kagame seems undaunted by anything, not even the prospect of a new war with the Congolese giant, whose surface area is almost a hundred times that of Rwanda. For two years, the spectre of open conflict has dogged relations between Kinshasa and Kigali. In March 2022, the M23 rebels went on the offensive in eastern DRC, supposedly defending local Tutsi minorities threatened by the Hutu FDLR. Despite the anger he arouses among the Congolese (the singer Gims, in his song ‘Thémistocle’, rhymes ‘Kagame’ with ‘croix gammée’, the French word for swastika), Rwanda's strongman yields on nothing. He no longer even bothers to deny the presence of Rwandan troops in the DRC. After all, inter-ethnic conflicts between Rwanda and Burundi have been bloodying the eastern borders of the DRC for three decades: In 1996, fed up with the cross-border raids by former genocide perpetrators who had taken refuge in Zaire and Mobutu Sese Seko's passivity, Kagame and his ally Museveni gave decisive support to Laurent-Désiré Kabila's rebels, who toppled Mobutu the following May (much to Paris's dismay). Rapidly disappointed by the new master of Kinshasa, Kagame became involved in the second Congo war in 1998, a full-scale continental conflict involving dozens of armed groups and troops from eight countries, which resulted in the deaths of around 3 million people in four years. Rwanda also took advantage of the conflict to benefit, via its local allies, from some of the mineral wealth of its Congolese neighbour, exporting coltan and tantalum.

FORMER SPYMASTER

Paul Kagame is first and foremost a soldier. And he is also an intelligence man, a characteristic he shares with Vladimir Putin, among others. Born in 1957 in Ruhango, Rwanda, he had to flee with his family to Uganda as a child to escape the first Tutsi massacres. When he was 20, the young Kagame joined the Ugandan guerrillas who, alongside Julius Nyerere's Tanzanian army, overthrew the volatile dictator Idi Amin Dada. When Dada was replaced by another dictator, Milton Obote, Kagame joined the rebels led by a certain Yoweri Museveni. In 1986, he returned to Kampala victorious, alongside Museveni, who remains head of state to this day. Propelled by his mentor, Major Kagame became head of the Ugandan army's secret services, and then president of the circuit court responsible for trying and sometimes sentencing to death Obote's henchmen. Together with other Rwandan exiles, he founded the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), with the aim of reclaiming his lost homeland. What followed is better known: an initial RPF offensive in 1990, which failed by a hair's breadth. François Mitterrand's increasing intervention alongside President Habyarimana. The increasingly racist radicalisation of Hutu Power, which saw every Tutsi, including women and children, as ‘enemies from within’ to be eradicated. And finally, the genocide machine, which exterminated around three quarters of Rwanda's Tutsis. When Paul Kagame took control of the country, it was destroyed. It was a gigantic open-air mass grave, where the survivors were forced to live alongside their neighbours and executioners. The exiles, often born in Uganda, formed the backbone of his regime. They turned out to be “much better educated, militarised and disciplined, the RPF’s ideal people”, as Gérard Prunier, a Great Lakes specialist, pointed out in an article for the Institut Montaigne back in 2018.

“I had to fight for everything”, recalls the President. “I wanted to break free, I wanted to take my destiny into my own hands and escape the vicious circle of violence and reprisals. This struggle has shaped who I am today”, he says emphatically, as if he were demanding the same energy, the same determination and the same discipline from every Rwandan citizen. And he is just as demanding of others as he is of himself, as Arsenal's players learned, the hard way. In August 2021, after they lost to a minor team, Kagame, who had sponsored the club since 2018, wrote on his Twitter account: “We must NOT excuse or accept mediocrity. A team must be built to win, win, win.” “Paul Kagame is chilling,” reckons Antoine Glaser. “When he speaks, you can feel the past of a man deeply marked by the genocide, as well as by his training as an intelligence officer: he trusts no one.”

“SERVE FOR AS LONG AS POSSIBLE”

However, it has to be said that he has enormous self-confidence and feels invincible. In de facto power since July 1994, Rwanda's strongman was elected president in 2003, re-elected in 2010 and again in 2017, winning more than 90% of the vote even more than Vladimir Putin. On 15 July, the 66-year-old will stand for another seven-year term. He recently confided that he was “ready to serve the Rwandans for as long as possible”: the Rwandan constitution, amended in 2015, gives him the right to do so. “The international community, trapped in its remorse and seduced by the progress made, is acquiescing”, was Gérard Prunier’s analysis back in 2018. But opponents are dying violently or disappearing without a trace. Paul Rusesabagina, the Hutu manager of the Hotel des Mille Collines during the genocide, saw his story romanticised and embellished on screen in 2004 in the American film Hotel Rwanda, for his role in the rescue of more than a thousand Tutsis. This critic of the regime was sentenced in 2021 to 25 years in prison for ‘terrorism’, before being pardoned, under pressure from the United States, country of which he is a citizen. Exiled in the USA, he believes that “Rwandans are prisoners of their own country”.