The metamorphosis of Akouédo

It’s almost in the heart of Abidjan. And for a long time, Akouedo, was one of the region's most toxic landfills. After being closed in 2018, it underwent an ambitious rehabilitation and has now morphed into the green lung of the megalopolis, open to the public. An example to follow!

Who would've imagined such an impressive reversal of fortunes – from notorious to glorious. Really. Bang in the middle of the Cocody district, in the hustle and bustle of Abidjan, a one-of-a-kind park is coming to life, a green oasis in a high-density urban environment. An outer city landscape, with trees, a botanical trail, and sports and play areas. Soon, in just a few weeks, it'll be open to the city's inhabitants. It's a real revolution, when you consider the state of the place not so long ago. Akouédo started life in the 1960s as a landfill site with a grim reputation. For decades, it was virtually the only waste disposal site in Abidjan, and one of the largest in Africa. A highly toxic area, with no waste sorting system whatsoever, gradually absorbed by urban sprawl, with people setting up home nearby, an ecosystem of misery, a massive public health and environmental hazard.

In 2006, it was further marred by the Probo Koala tragedy, a waste ship whose highly toxic waste was dumped on the site, causing a major disaster. On this 112 hectare site, more than 80 hectares were completely filled with all kinds of waste. Given the scale of the problem, the Ivorian authorities decided to close the landfill in 2018 and launched a particularly ambitious rehabilitation project that included waste management and the development of a park and open spaces for the public.

A project crazy in scale and scope in terms of the technological challenge it involves, funded by the State and awarded to PFO Africa, the company run by architect Pierre Fakhoury and his son Clyde. They threw themselves wholeheartedly into the project, joining forces with Veolia (waste treatment expert), large-scale landscaper Gregori International and landscape gardener Philippe Niez (Niez Studio). It was the start of an extraordinary adventure. The site was secured and millions of tonnes of waste were confined by reshaping the embankments. Peripheral pits were created for rainwater drainage.

The whole is covered with a secure, watertight geomembrane to prevent any leakage or toxic seepage. The biogas and leachate produced by the gradual fermentation of the waste are captured by recovery wells, as well as a sprawling surface collection and transport network. The biogases are transported to a cogeneration plant. This on-site power plant meets the park's electricity needs, with the surplus being fed back into the national grid. The leachates, meanwhile, are treated and decontaminated. And the purified water is returned to the Ebrié lagoon.

A RADICAL ECOLOGICAL CHANGE

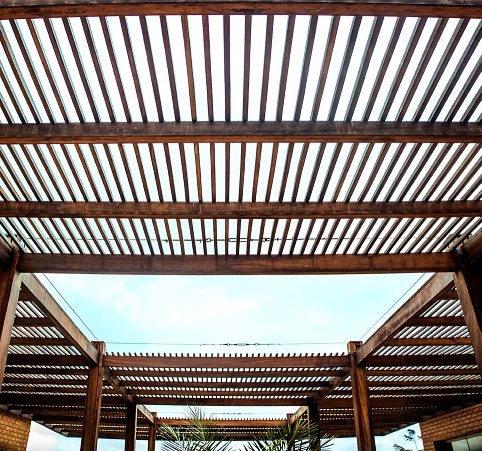

The complex has been designed as three zones. Zone A, now stabilised, will be open to the public. Zones B and C will gradually become accessible as they are stabilised. Zone A includes the leisure areas and an environment centre. And, as the project's centrepiece, a large botanical park designed by landscape architect Philippe Niez. A huge nursery has been set up, drawing on the experience and expertise of people who have lived near the site. Visitors will be able to take a walk through these Ivorian plant worlds via a 60-metre-long, 1-metre-high, secure footbridge built to preserve this reborn natural environment. They will cross the forest of giant trees and discover the savannah area and its tall grasses, before arriving in the Makoré forest (and its rare species). Akouédo has been awarded the 2021 Circular Economy Grand Prix by Geste d'Or, an independent building trades association. And today, despite the impact of the Covid epidemic on the construction work, the park is almost ready to open. Which is quite a challenge!

The challenge in Akouédo's radical transformation goes beyond the site itself. The issues of waste and sanitation, and the protection of forests and natural areas are strategic. Abidjan's famous Banco National Park, a 35 km2 green lung for the city, is under threat from urbanisation, illegal logging, pollution and more.

Urban landfills are legion on the continent, and remain a major blight on the environmental security of large African cities. They also have an exorbitant carbon footprint. Over the 2000-2021 period, greenhouse gas emissions from waste in Africa increased almost twice as fast as overall emissions, accounting for around 8% of the total. The issue of sanitation remains equally crucial (only 300 million Africans have access to adequate facilities, according to the WHO). The experience of Akouédo and that of Cote d'Ivoire could therefore prove particularly useful to others.