An Ivorian Promise

This October, the presidential election will be held.

It will be the country's twelfth presidential election, and above all the sixth since 1990 and the advent of a multi-party system. In a still fragile democracy, in a great country of promise and opportunity, the election of a ‘leader’ is a major political event, one that has not been without identity crises and divisions in the past. A major episode for a now fully emergent Côte d'Ivoire. A moment of truth regarding the new capacity to live together, a decisive moment for the process of democratic consolidation and the acceleration of development.

It will be a historic, pivotal moment for the ‘leader’, Alassane Dramane Ouattara. This son of Kong has been in power since 2011, after a long political journey. He is inextricably linked to the country's modern history, the architect of the second economic miracle and the new institutional mechanisms. It is his project and his life's work. The election will require an assessment of the situation, as well as a look to the future and the design of a new cycle.

And he will also have to decide. Whether he is a candidate or a candidate maker, and how he will be central to the episode.

In fifteen years, as previously mentioned, the country has changed profoundly. Côte d'Ivoire has achieved one of the few true emergence paths in Africa over this time. Its growth is one of the fastest in the world (7% on average), even during the terrible Covid ordeal (with a very slightly positive rate in 2020). Its economy has become one of the top ten on the continent. The country has been built, physically transformed, and metamorphosed. Not only with roads and bridges, but also with schools, colleges, universities, health centres, teaching hospitals, and more. Abidjan enjoys credibility on the international markets, the Ivorian signature is ‘worth’ something, Côte d'Ivoire remains the world's leading producer of cocoa, an agricultural powerhouse, and it is getting involved in oil and gas production.

The change goes beyond the frame of reference of a purely economic analysis. Despite ethnic and cultural differences, real divisions that can be rekindled and fuelled by cynics, particularly during political episodes, there is a growing sense of an Ivorian vision (see pages 70-75), the concept of a common nation being built, of a shared destiny. There is a sense of a desire for unity in diversity, a desire in any case not to fall back into the throes of division. To protect what must be protected. And the Africa Cup of Nations (February 2024), a true moment of collective achievement, showed that enthusiasm for the flag was more than possible – of course, it's easier with football, a miracle at the halfway stage and a final victory at the end.

While Côte d'Ivoire is not yet a great, solid democracy (do any great, solid democracies still exist in the world?), institutional progress is real, with texts, jurisdictions and processes. The last legislative (March 2021) and municipal (September 2023) elections were open and transparent. The president is the president, that much is clear. He decides and he arbitrates. However, the system has multiple inlets. With competition in the spheres of power. A media society, a civil society, a debate, politicians, opponents who express themselves. It is lively and vibrant.

And then there’s security. This luxury of contemporary Africa. The Grand-Bassam beach resort attack (13 March 2016) left a lingering wound. Since then, however, the country has invested heavily in equipment, intelligence, training and upgrading of the security forces (army, police, gendarmerie). The fragile regional situation, the risks to integration, and the more or less open crises with neighbouring Sahel countries are creating new challenges. Even though the state of alert is permanent and the worst is always possible, and the jihadist danger is particularly worrying, the borders are being guarded. Security also means a sense of everyday peace of mind. One can travel around the country, drive - even at night - go visit cousins or family, head out into the city at night, in Abidjan or elsewhere, and go to the beach or the forest. As everywhere, there are risks, but these are managed in a surprising state of normality.

All this could almost seem normal today. Something that goes without saying. However, it is worth repeating that the country has come a long way. It has had a brutal past. The death of the founder Félix Houphouët-Boigny (December 1993) led to a cycle of unrest, institutional and economic crises, and the rise of ‘ivoirité’, a toxic nationalist concept. The mirror shattered in December 1999. President Henri Konan Bédié was overthrown in a (Christmas) coup. Laurent Gbagbo came to power in October 2000. In September 2002, the country was split in two following a rebellion. The crisis reached its peak with the presidential election of November 2010 which, since 2005, had been postponed several times. Laurent Gbagbo refused to recognise Alassane Ouattara's victory.

In the aftermath of that last tragedy, Côte d'Ivoire was bled dry, ruined and deeply divided, as if emerging from a civil war.

And yet, over the next two or three years, the country was back on its feet, people came together again, worked and lived together. The reconciliation was gradual, but it was achieved largely without coercion or violence. Of all of President Ouattara's achievements, this particular period was certainly the most historic and the most revealing, as one informed observer pointed out.

Nothing is simple, of course. Despite visible progress, inequalities and geographical disparities are prevalent. Inclusivity remains a priority. Population growth and immigration, still strong, bring their share of opportunities, but also constraints. The effects of climate change could disrupt future growth patterns. And faster progress is needed in terms of ‘clean’ industrialisation, sustainable development, job creation, private sector mobilisation, and adaptation to new technologies and the world to come. But these ‘musts’ do not change current reality. On the map of the continent, there are still too few places where ‘we believe’, with relative optimism about the future, where we sense dynamism, ambition, and ‘weight’.

At the centre of the equation, of course, is President Alassane Dramane Ouattara. The country is governed. There is a plan. A will. A path, too. ADO forged ahead in the face of adversity and opposition, creating a party (the RDR), mobilising the troops, mobilising a close guard of lieutenants and loyalists. Some of them departed far too soon, like Amadou Gon Coulibaly, the true political heir who passed away in July 2020 and Hamed Bakayoko, who died due to illness in March 2021.

The president is surrounded by a supportive team. It matters. He works hard and it matters. He is clearly the patriarch, he insists on respect for precedence, he can be temperamental (but has a sense of humour too). However, beyond the power, there is this underlying and constant desire to make his mark, to feel that he has done something, that he has implemented a true African model of emergence, that he has achieved a result. For ADO, heritage and legacy, as the English-speaking world would say, are essential. And so he must be the captain of the ship, he must protect Cote d'Ivoire from dangers and threats. He feels responsible, and the future will not be written without him.

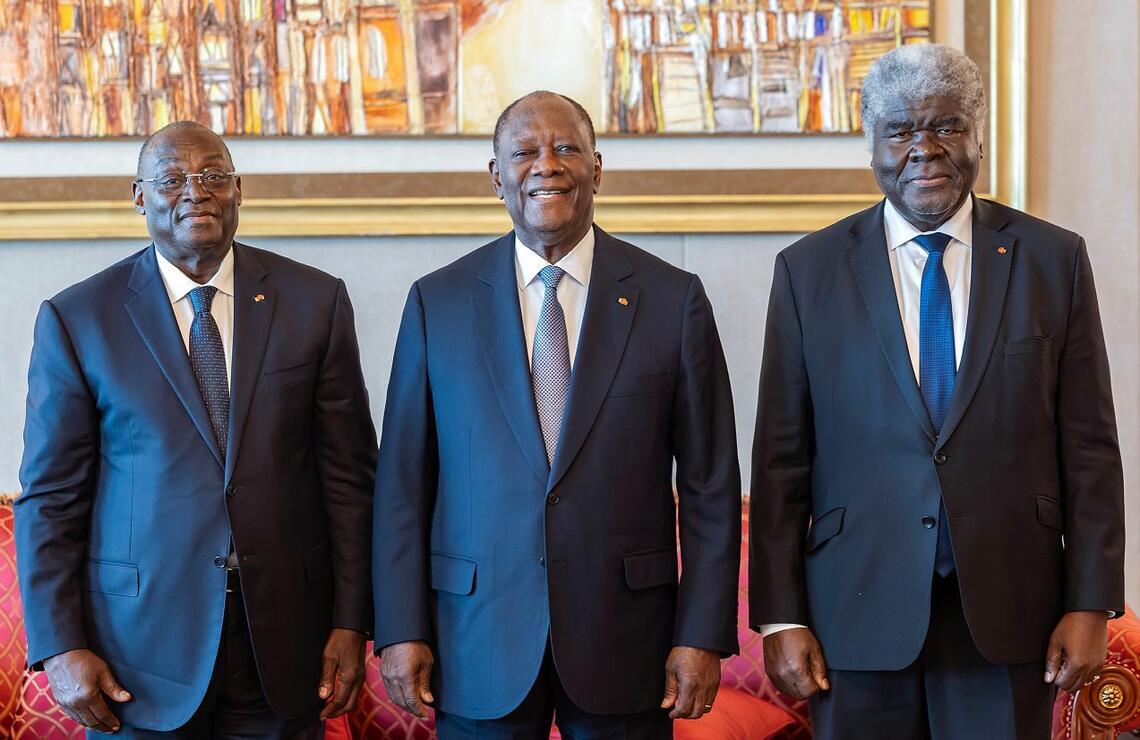

Of all the possible scenarios, that of a ‘quiet withdrawal’ is highly unlikely. Whether as an inspiration or a player, he will central to the October 2025 electoral equation. Ado is refining his thinking. Mulling over his decision. During his New Year's address to the government, he pointed out that there are indeed half a dozen people in the room who could apply. He has placed his trust in his vice-president, Tiémoko Meyliet Koné, an experienced man. In his Prime Minister, Robert Beugré Mambé. In the party, in the government, the heavyweights are lined up, ready to act.

The election will not be a formality. It's too important a moment. There will be debate, there will be competition, there will be personality clashes with, inevitably, a look towards the generational transition. The opposition is far from silent. Some potential candidates are determined to go for it, one way or another. With their well-affirmed certainties and their weaknesses. Tidjane Thiam, the former international banker, who took the PDCI (Democratic Party of CIV) by storm, firmly believes in it, despite his long absence from the country and the divisions in his camp. Laurent Gbagbo is out for revenge, no matter what, and his natural place in history. Mavericks like Jean-Louis Billon, and others, will seek to confuse the scenarios.

However, the stakes involved are higher than personal destinies and adventures. Côte d'Ivoire is on the road to emergence, a rare and fragile process. Evolution and development are not irreversible achievements. The virtuous circles of growth, democratisation and stability are not preordained. The challenges are there and must be met collectively. With 70% of the population under the age of 30, these new generations need to be involved, to buy into the model and to believe. More than ever, we must definitively break free from conflicting ambitions and truly rise above regional or religious affiliations. More than ever, we must show that we are modern. We must promote essential political dialogue, collectivity and openness.

The stakes are high. President, political class and citizens are all committed to the deadline. There is an Ivorian promise to keep, the possibility of relying on the country's rather astonishing ability to bounce back, to build itself, to project itself, to move forward.