Horn of Africa

Abiy Ahmed's power moves

The quest for access to the sea via breakaway state Somaliland, energy sovereignty by means of a major dam on the Nile... Ethiopia's Prime Minister, winner of the 2019 Nobel Peace Prize, wants to reassert his country's dominance and give his deeply divided people a common ideal. At the risk of losing investors, falling out with his neighbours and setting the whole region ablaze.

It's hard to imagine that the man who uses this kind of language is the same man who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2019 for his short-lived reconciliation with Eritrea and his no less short-lived openness to democracy: “We won't negotiate with anyone on Ethiopia's sovereignty and dignity. We will not allow anyone to harm us, and we will humiliate anyone who dares to threaten us. Any country should think not once, but ten times before attacking Ethiopia”, warned Abiy Ahmed, more strident than ever, on 9 September, Ethiopian Sovereignty Day.

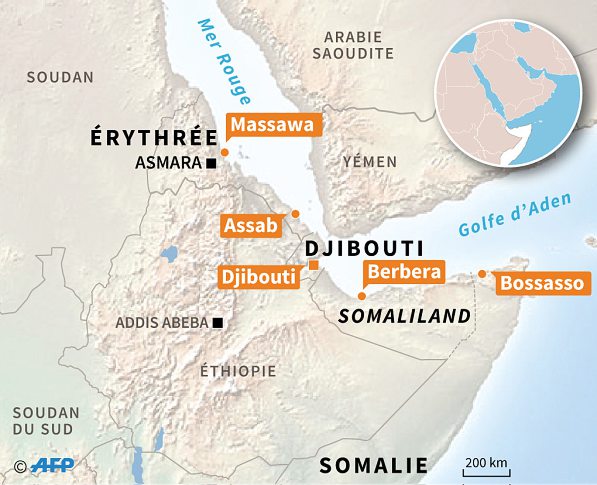

Ten months after signing a memorandum of understanding with Somaliland on 1 January to create an Ethiopian maritime outlet on the coast of this seceded Somali province, Abiy Ahmed persists: he wants to put an end to the country's isolation. His historic mission is to free his people from what he has described as a ‘geographical prison’. It matters little to him that Somalia – which has never accepted the secession of the former ‘British Somalia’ – feels attacked and has formed a military alliance with Egypt, which has been at loggerheads with Ethiopia since the construction of the mega-dam on the Nile. Despite the threats of war, he seemed determined not to make any concessions: Ethiopia intended to obtain naval, trading and military facilities on the Red Sea coast. Even if it meant recognising Somaliland's independence and creating an unfortunate precedent on the continent, to the great displeasure of the African Union, which has its headquarters in Addis Ababa!

This determination is as much directed at Egypt, Somalia and Eritrea (with which Ethiopia is once again at loggerheads) as it is at the 120 million Ethiopians, to whom the Prime Minister wants to restore a sense of national unity that transcends ethnic and religious divisions. Abiy Ahmed is probably less afraid of an open war with his neighbours than of a worsening of the country's internal troubles. Almost two years after the end of the appalling Tigray war, Ethiopian unity remains more threatened than ever. As a reminder, the conflict with the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF, whose elites dominated the country from the 1990s until Abiy took power in 2018) caused the deaths of at least 600,000 people between November 2020 and November 2022, at a cost of 28 billion dollars. The federal Ethiopian army allied itself not only with the autocrat Issayas Afewerki's Eritrea (which borders Tigray to the north), but also with the nationalist militias of the Amhara region (which borders Tigray to the south): the Fanos, whose name, ‘volunteer fighters’, comes from the Amharas mobilised in the 1930s by the Negus to resist the Italian invaders. In April 2023, however, the Fanos refused to disarm for fear of losing the territorial gains they had made at the expense of the Tigrayans, particularly in the disputed Wolqayt zone. The nationalist militiamen took up arms against the federals, even briefly seizing (in March) the regional capital Bahir Dar, emptying the prison of its inmates and attacking Lalibela airport. The federal army responded to the insurgents with drone bombings and arrests, and even summary executions, of young Amharas suspected of joining the guerrillas (around a hundred dead in Merawi on 29 January, according to NGO Human Rights Watch). This counter-insurgency strategy, the excesses of which have strengthened support for the rebels, who have the backing of popular opponents such as the dissident journalist Eskinder Nega.

The situation seems inextricable: the Amhara region, the historic heart of Ethiopia (population 30 million), is escaping central control. This insurrection comes on top of an older one by the OLA, the Oromo Liberation Army, in the Oromia region (population 35 million). During the Tigray war, the OLA formed an ad hoc alliance with the Tigray Defence Forces (TDF). Now the OLA is opportunely turning to the Fanos, despite the conflicting demands of the two rebel movements! “The Amhara populations established on Oromo soil are perceived by the more radical Oromos as settlers from within”, explains Éloi Ficquet, a Horn of Africa specialist and senior lecturer at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales (EHESS). “The Amharas believe that it is legitimate for them to settle outside their region of origin. The Oromos are more localist and aim to win power locally. More than an independent Oromo state, they aspire above all to control the resources of the local economy.”

Armed struggle and banditry

Aided by a profusion of light weapons (the famed AK-47), armed groups are proliferating, often oscillating between political demands and organised crime (roadblocks, kidnappings and racketeering). “This type of action has given rise to vocations”, continues Éloi Ficquet. “The armed groups that engage in it receive something in return for stopping their abuses.” Their power to cause harm is such that around a third of Ethiopian territory is no longer under state control. This has obviously had an impact on the economy: “The free movement of investors, traders and students was the strong argument for the peace brought about by the federal regime”, recalls Éloi Ficquet. He points out that today there is a retreat into identity politics, with people feeling insecure outside their ethnic territory. “The federal regime had authoritatively re-established a deep level of state control, which has now vanished. Restoring sovereign authority will be a challenge. But the regime can benefit from this chaotic situation by presenting itself as the only bulwark capable of restoring order.”

Pending an overhaul of federalism

Ultimately, Ethiopia will not escape a debate on its institutional future. Abiy has succeeded in satisfying the south, with the Sidama region (June 2020) and the South West Regional State (November 2021) which, after referendums, have become autonomous from the Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples Region (SNNPR). “Discussions on possible institutional reform point to the fragmentation of the federal map, with the territorial scale coming to the fore in relation to the ethnic scale”, says Éloi Ficquet. “We are seeing territorial fragmentation and the reconfiguration of a federalism that no longer appears to be based on a broad ethnic territory, but rather on territorialities corresponding to identities that are sometimes very old”, he explains. This development would enable Addis Ababa to reshuffle the cards in its favour: “We can envisage a form of re-emergence of this old map of power, in order to satisfy (and control) certain local elites. This could have the advantage, for Abiy, of dislocating the identities of the traditionally dominant groups (Amharas, Oromos, Afars, etc.) by satisfying the political groups, who can then hope to gain power in the local political game.” It's not a new strategy, says the expert: “It's like the old political game of the Ethiopian empire.”

Pending an overhaul of federalism, and faced with the imminent risk of dislocation, the Prime Minister wants to offer Ethiopians a unifying national project. He wants to show them that what can unite them – the Ethiopian national idea, sovereignty, economic development – transcends these ethnic and religious divisions, the violence of which is jeopardising their physical security and economic well-being. Hence his obsession with restoring Ethiopia's access to the sea, lost in 1993 when Eritrea gained independence. “This, too, is an old strategy in Ethiopian politics: to revive the nationalist fibre in a situation of regional conflict”, says Éloi Ficquet. “Appealing to the higher national sentiment, which would be shared by the various ethnic groups – and in particular the Amharas, the population at the heart of the national project. The restoration of access to the sea, legitimised by ancient historical borders, is an old Ethiopian nationalist argument.” During the conflict with Eritrea (1998-2000), nationalists wanted to reclaim the port of Assab. The demand for access to the sea ‘was already a mobilising issue for opponents of Meles Zenawi’, Prime Minister from 1991 to 2012. And they are ‘part of the circle of power around Abiy, in particular Berhanu Nega’, a former opponent, co-founder of Ginbot 7 and leader of the CUD (Coalition for Unity and Democracy), which claimed victory in the 2005 elections in Addis Ababa.

Powering bitcoin factories

Abiy's determination to implement the GERD (Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam) follows the same logic as that of regaining access to the sea. Initiated under Zenawi, this dam, 145 metres high and 1.8 kilometres long, “should give Ethiopia the means to develop a truly independent industrial policy”, explains Éloi Ficquet. Since international financial backers were unwilling to subscribe to the mega-project, which was seen as destabilising for the Horn because of fierce opposition from Egypt and Sudan, its completion, through more or less voluntary conscriptions, is proudly presented as a show of sovereignty.

“GERD's mission is to provide jobs for young graduates and to respond to the frustrations expressed on ethnic grounds. It's a form of modern comfort that matches the very strong ambitions of the Prosperity Party (PP), whose name is unequivocal”, explains Éloi Ficquet. In late August, Ethiopia announced the doubling of GERD's output, thanks to the commissioning of two 400 megawatt turbines, in addition to the two 375 MW turbines due to come on stream in 2022. Electricity production now stands at 1,550 MW, and should eventually exceed 5,000 MW with thirteen turbines. Despite the risk of war, the priority is economic development and energy sovereignty, in the face of a petroleum product demand that is rising by 10% every year, costing Ethiopia around €6 billion in fuel imports. The country is the first in the world to ban the import of internal combustion engine vehicles. Abiy Ahmed wants, in the medium term, to have all citizens driving electric vehicles. Currently there are around 100,000, but the number is expected to quadruple by 2030, thanks in particular to imports from his ally China. It doesn't matter to him that the country currently has ‘only one public charging point’, and that spare parts for electric vehicles are still ‘hard to find’, according to Le Monde (September 10)! “The Ethiopian government is no stranger to making this kind of abrupt decision, the implementation of which is fraught with problems”, points out Éloi Ficquet. One in two Ethiopians has no electricity. But widespread access to electricity hardly seems to be the prime minister's priority: Ethiopia has indeed become host to ‘bitcoin farms’. Around twenty companies, most of them from China, where they have been banned since 2021, are setting up in the country to mine cryptocurrencies using supercomputers, which consume a lot of electricity. The paradox is that Ethiopians are theoretically banned from using cryptocurrencies! But who cares? It's all about bringing foreign currency into a country that Washington has excluded from the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), the US-Africa free trade agreement, since January 2022, because of ‘gross human rights violations’ in Tigray.

The 2019 Nobel Peace Prize winner's star has therefore waned considerably in Washington, as it has with international donors. In April 2018, when this young, unknown Prime Minister came to power, he raised many hopes in the chancelleries because of his lifting of the state of emergency and the amnesty granted to political detainees at the time. However, Abiy Ahmed, 41 at the time, came to power by default, for want of another candidate. Faced with an Oromo insurrection around Addis Ababa, the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF, the coalition in power since the fall of Mengistu in 1991) was looking for a moderate Oromo who would calm the protesters without imploding the country. Abiy Ahmed, a Pentecostal Oromo with a Muslim father, married to an Amhara woman, a former Minister of Science, a lieutenant-colonel in the intelligence service, a veteran of the guerrilla war against Mengistu as a teenager and then of the war against Eritrea, seemed to meet all the EPRDF's criteria, so that everything would change without anything changing. After purging power from the Tigrayan elites (with the consent of the population, which hated them), he “surrounded himself with a political and economic elite that had emerged during the Zenawi era. A political and economic clientele, mainly Oromo, whose resources and privileges have been strengthened in recent years”, stresses Éloi Ficquet. “Abiy Ahmed has promoted people in the civil and military administration who owe their careers to him and are totally devoted to him”, explains historian Gérard Prunier, a specialist in the Horn. “Even if a large part of the country falls apart, control of the capital and the central regions is enough for them”, continues Éloi Ficquet. “The current system of power is based on a pyramid cemented by predation, extortion and corruption. It's a transactional pyramid, because each level that is given the power to enrich itself has to pay back part of its gains to the next level up, and so on”, concludes the researcher.

Overcoming all obstacles

Despite coming from a modest background, Abiy had a colossal 500-hectare palace built on Mount Entoto overlooking Addis Ababa. The capital which, in thirty years, has doubled its surface area, has seen an increasing number of expropriations from small landowners, without prior notice or adequate compensation, in defiance of Ethiopian law. The Pentecostal Abiy “has always championed a messianic vision in his speeches, guided by religious ideals”, explains Éloi Ficquet. He knows that his ideal of prosperity will not be achieved without difficulties, but insists on his ability to ride out the storms. This can be seen in the mammoth investments made in Addis Ababa to build a gleaming model that is supposed to convince the old world to embrace it. The guide, who considers himself a visionary anointed by the Almighty, knows where he is going and must continue his work... even if it is, for now, misunderstood!

This way of thinking, explains Ficquet, “is a dialectic of overcoming, even if it means creating a security vacuum...” Djibouti is also worried about this resurgence of regional tensions: “The Ethiopian enclave in Somaliland is facing rejection from the people of the region,” says a senior source in Djibouti. “It could get out of hand. It's also a problem for our country, which would find itself with a new Ethiopian border.”

The stretch of coastline in Somaliland, where Addis Ababa's authorities intend to build a commercial port and naval base, would be connected to Ethiopia by a road corridor “very close to the border”, worries our Djibouti source. “Historically, the Red Sea ports have always negotiated various types of tax benefits in order to obtain privileged access to the caravan routes”, recalls Éloi Ficquet. However, the experts interviewed have little faith in the possibility of open warfare. “Egypt is not in a position to do that”, says Gérard Prunier. “It would like to get involved, but it doesn't have the capacity to project troops from a distance. As for Somalia, the government in Mogadishu only controls around a hundred kilometres of territory around the capital. So Abiy knows he has nothing to fear...”

Threat of proxy wars

Éloi Ficquet says: “I don't see Somalia going to war. As it is, Mogadishu has no means of dictating its will to Somaliland”, which has been de facto independent for over three decades. Similarly, “I don't see Ethiopia going to war either, when it is unable to contain the rebellions in the Amhara and Oromia regions.” But “the regional conflict is already there”, says Éloi Ficquet. “The risk is that it will escalate.”

The experts lean more towards proxy wars, which countries in the Horn are used to: financing insurgents in the opposing country in order to destabilise it... “These armed groups can cause unrest, but they are not in a position to establish a parallel administration, let alone overthrow the central government. Somalia, rather than intervening militarily in Ethiopia, can destabilise it via armed groups on Ethiopian soil.” Ethiopia has around 4% Somali citizens. “Eritrea, which supports Oromo and Amhara groups, has often supported Somali armed groups in order to destabilise Ethiopia.” Erdogan's Turkey, which has a strong presence in Somalia, is looking for a diplomatic solution to defuse this powder keg. At the beginning of August, Hakan Fidan, the Turkish Foreign Minister, welcomed the ‘notable progress’ made in these negotiations. A third round of negotiations (Grand Mediation and Peace in the Horn of Africa) was held in Ankara in mid-September. One of the avenues being explored is for Somalia itself to act as an alternative, bypassing rebel Somaliland by offering Ethiopia port facilities! “I'm not sure that Somalia could concede Ethiopia complete autonomy in naval military terms”, says Éloi Ficquet. “Ethiopia wants to be seen as a global player; it has joined the BRICS. It wants to get its navy back.” Gérard Prunier, when asked about Somalia's way out, exclaims: “It's just pie in the sky.” The historian points out that the United States, a former ally of Ethiopia in Zenawi's time, “could intervene diplomatically, but they are paralysed by the elections. Nothing will happen before the presidential inauguration in Washington on 20 January 2025.” In late August, Ethiopia took a further step towards formal recognition of Somaliland's independence: a diplomat presented his ‘credentials’ to the Somaliland authorities in Hargeisa, the de facto capital of the self-proclaimed state. “If the Ethiopians had wanted to recognise Somaliland, they would already have done so”, says our official source in Djibouti, who stresses that “recognition of Somaliland would also create a precedent. This could have a knock-on effect on Ethiopia, with internal secessions!”

Djibouti is another key regional player. The republic has positioned itself as a crossroads for trade and stability in a fractured environment. And for the government, maintaining a minimum of regional balance is an imperative. Ethiopia is an essential partner. The port city handles 90% of Ethiopia's imports and collects around 1.5 billion dollars in port charges and duties. At the same time, however, the Djiboutians make no bones about their scepticism regarding the planned corridor in Somaliland, 20 kilometres of coastline leased for half a century, where the Ethiopian government intends to build a commercial port and a naval base, and which would be connected to Ethiopia by a road corridor. As well as being particularly close to their border, Djibouti points out that the project is strongly contested by the local population, who allege illegal dispossession, as the resignation of the Somaliland Defence Minister, a native of the region, dramatically demonstrated.