Estevanico, the first

African explorer of the new world

Doctor of History Marc Terrisse took an interest in the life of this incredible trailblazer, tracing his life from Morocco to Arizona.

In the early 16th century, a Spanish conquistador expedition to the coast of Florida was shipwrecked. Among the handful of survivors was Estevanico, a slave born in Azemmour, Morocco. His talents as a healer, no doubt inspired by the traditions of the Moroccan Gnaouas, enabled the survivors to cohabit with the First Nations, move from one village to another and stay alive. It took them around ten years to return to the Spanish colonies in Mexico, exploring the entire area of what is now the south-west of the United States along the way! On their return, based on Estevanico's reputation among the natives, the Spanish authorities asked the Moroccan to act as guide on a second expedition, which probably proved fatal. We interviewed historian Marc Terrisse, who retraced the steps of this little-known African explorer from Morocco to Arizona.

AM: How and why did you become interested in Estevanico?

Marc Terrisse: I discovered Estevanico through the research I did for my previous book on the Arab community in New York (New York, Portrait d'une Ville Arabe, Éditions Bibliomonde, 2023). For Arab Americans, Estevanico, who came to Florida in the early 16th century was, in a way, the first of them. So I investigated that century. Estevanico, a Moroccan, African and Muslim slave, was thrust unwillingly into protocolonialism in the Americas.

What do we know about the role played by Estevanico in the small group of survivors of the 1527 expedition?

The sources are the ‘accounts’ (written reports) of the three surviving conquistadors: Cabeza de Vaca, whose text has become a literary classic, Dorantes, Estevanico's master, and Del Castillo. Estevanico is most often described as ‘the black man’... But in the writings of his master Dorantes, there is a certain closeness, a form of affection. Initially used as a military auxiliary, he went on to play a more important role: that of a shaman offering his services to the natives. There are clear analogies between the Spanish descriptions of Estevanico's treatments and the practices of the Moroccan Gnaouas, who are descended from sub-Saharan slaves! It was his talent and interpersonal skills that enabled the little group to survive. Because of his background, he must have had a certain facility for languages: he spoke Arabic or Berber, and had to learn Portuguese and Spanish. Above all, he learnt to live in different environments and to adapt to them: the Spanish sent him ahead to make contact with the local people.

You point out that many Africans joined the conquistadors, often in spite of themselves...

A great many Africans accompanied the Spanish and Portuguese conquistadors from the 16th century onwards. There were lots of slaves in Seville and Lisbon, in particular, where they worked as servants and military auxiliaries. Among them, Juan Garrido, who accompanied Cortés on his Mexican expeditions, is probably the best known.

In your book, you state that many foreigners abducted or adopted by the First Nations chose to stay with them, because of the freedom and egalitarianism that prevailed in indigenous societies. So why didn't Estevanico leave the Spanish?

One hypothesis is that he had close ties with his master Dorantes. He probably didn't want to abandon him. The three Spaniards, deprived of Estevanico, their intermediary, interpreter and healer, would probably not have survived very long. After a decade of roaming, they managed to return to the Spanish colonies in Mexico. But Estevanico was soon sent back north to lead a second expedition, in 1539, this time in search of the ‘Seven Cities of Cibola’ (a myth quite similar to that of El Dorado), with a monk named Marcos de Niza. During this expedition, it became clear that Estevanico was planning to emancipate himself: Dorantes wasn't around anymore, so he no longer had to look after him... He was sent as a scout and was clearly appreciated by the natives, who recognised him or had heard of his gifts as a healer: he had become a mythical figure.

During this second expedition, he was killed by Zuni Native Americans.

The main source of information on these events is the account of Marcos de Niza, the monk who organised the expedition in search of the legendary cities of Cibola, which ended up being modest villages. The continent's First Nations, frightened by the greed of the conquistadors, got rid of them by telling them that, further away, there was a city full of gold (‘Eldorado’ in South America, ‘Cibola’ in North America) that the invaders never found, because it didn't exist! Estevanico had got ahead of Marcos de Niza, and was sending him messengers to lead him here and there, as if trying to lead him astray. The monk writes that Estevanico was killed by a Zuni arrow outside the entrance to 'Cibola': the Zunis had ‘not appreciated Estevanico's behaviour towards their women’. Although Estevanico had a good reputation among the natives, he also opened the way for dangerous invaders. The First Nations travelled a great deal: excavations have found objects far from their production sites. The region of what is now Arizona was involved in trade and cultural exchanges with the Aztec empire, which was conquered and destroyed by the Spanish in 1521. The Zuni eventually learned what had happened to their neighbours to the south: Estevanico and his companions therefore represented a threat. But Estevanico's body was never found: it would have been easy for him to spread the word of his death and start a new life among the indigenous people!

You say that Estevanico is well known in Morocco.

He is the hero of several Moroccan novels: Le Fils du Soleil, by Hamza Ben Driss Ottmani, and The Moor's Account, by Laila Lalami, who imagines the story of his travels that Estevanico might have written himself. In 2013, he was the theme of the Remp'Arts street art festival in his home town of Azemmour, where he is increasingly celebrated as a Moroccan Christopher Columbus. Morocco was the first country to recognise the independence of the United States! Relations between the two nations are therefore long-standing and deep-rooted.

You also reveal that Estevanico is just as famous in the United States.

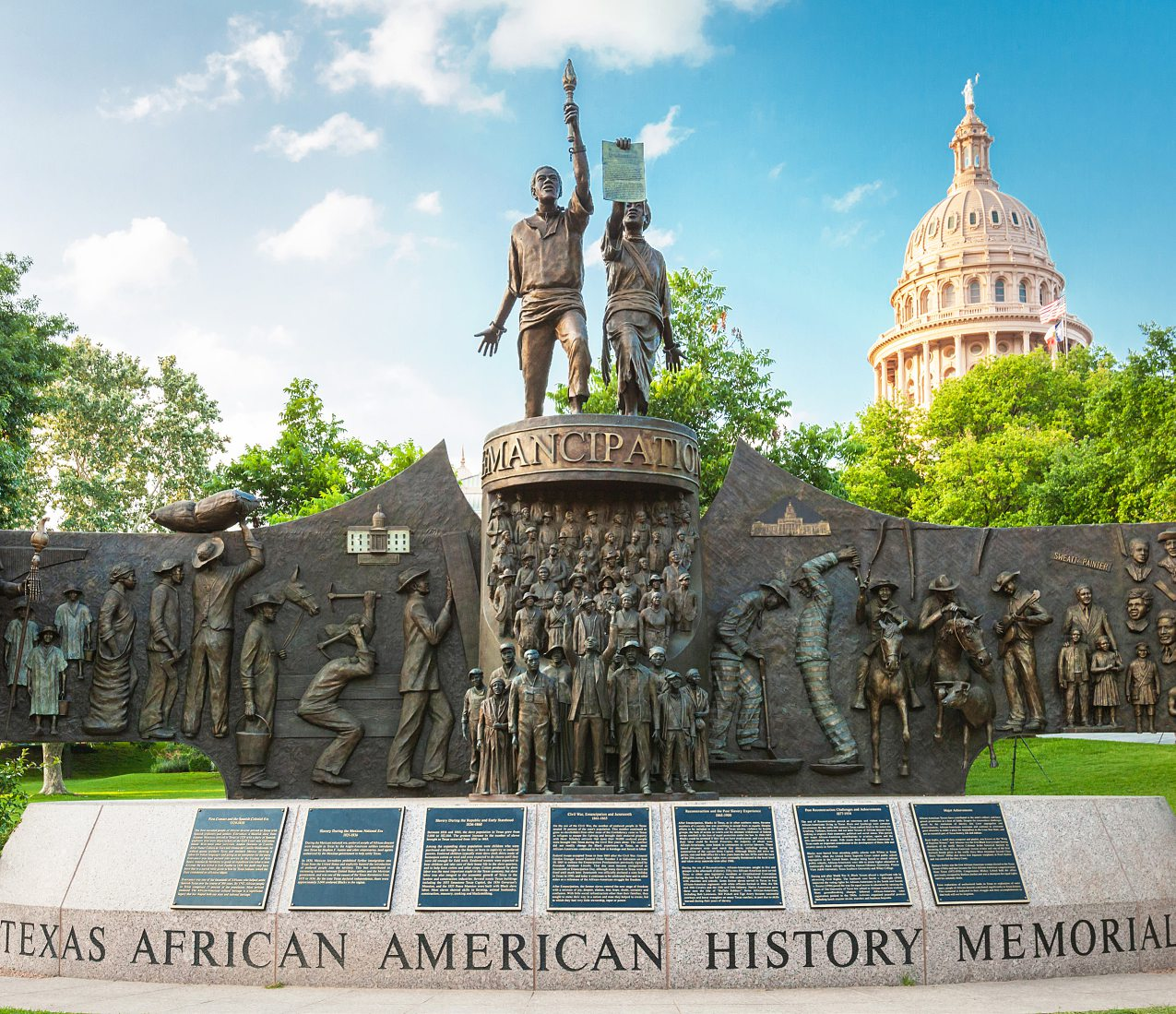

There's a whole mythology around the figure of Estevanico in African-American culture, which has put him in the spotlight since the struggles for emancipation and civil rights in the 1950s and 1960s. After all, he was the first African to explore what became the American South. Numerous novels written by African-Americans have featured him: Elizabeth Shepherd’s The Discoveries of Esteban the Black in 1970, Helen Rand Parish’s Estebanico in 1974. In 1986, Carolyn Arrington published a fictionalised biography for children entitled Estevanico, Black Explorer in Spanish Texas, while Mac Perry's Black Conquistador: The Story of the First Black Man in America was published in 1998. In 1996, star basketball player Kareem Abdul-Jabbar published an anthology of biographies of black Americans esteemed for their courage, featuring Rosa Parks alongside Estevanico. In Austin, Texas, Estevanico even has his own statue in front of the Capitol! I saw it, and it's quite curious: he's depicted wearing a 'fraise', a noble garment worn by gentlemen in the 16th century.

Apparently, it even inspired a cartoon series popular with French-speaking audiences, Les Mystérieuses Cités d'or...

The character of Esteban in this cartoon is based on Estevanico, and the ‘Cities of Gold' are inspired by the myth of the Seven Cities of Cibola. Other adaptations are more recent: Netflix makes a discreet allusion to the Estevanico character in its animated series ‘Maya, Warrior Princess’, produced in 2021. In the third episode of the first season, it talks about an African-American magician working on the lunar island. The magician's staff is called Estephan, an obvious reference to Estevanico.

Estevanico's name is also still known at the Zuni reserve, where he is said to have been killed!

I went there and met its representatives, who confirmed that oral tradition, handed down from generation to generation, has passed on the memory of a black warrior who was a bit of a sorcerer. He had a positive image because of his reputation as a healer, but he was said to have been insistent with the women of the village, which led to his being killed. As for the cities of Cibola, the myth that the Conquistadors pursued in vain, they are nothing more than a pile of ruins in the middle of the desert.

Estevanico managed to juggle these different African, European and Amerindian worlds to get by, despite being a slave?

He was able to forge close links with his master Dorantes, which undoubtedly helped him to improve his lot. He was able to assimilate into the First Nations' daily lives, through his ability to learn languages and his medicinal knowledge. That's why his destiny has such universal appeal.