Climate change

The future is now

Despite emitting between 3% and 9% of the planet's carbon emissions, Africa is already suffering the effects. Floods, extreme heat, drought, rising sea levels, economic and human The time has come not just to take stock, but to implement effective solutions and achieve greater international justice.

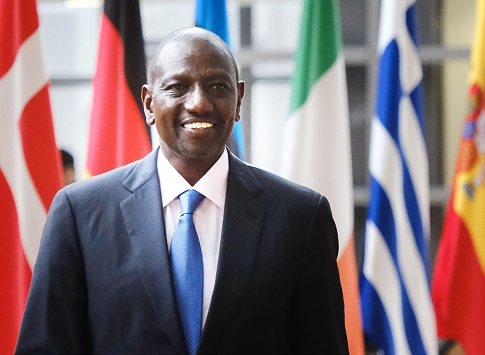

In East Africa, where torrential rains have devastated the region in recent months, several hundred people have died or gone missing. These catastrophic rains came on the heels of three years of equally catastrophic drought, in a deadly cycle that is exhausting the population, with the most vulnerable being the hardest hit. During his meeting with some twenty heads of state in Nairobi on 29 April, Kenyan President William Ruto used the occasion to demand “immediate and collective action for our planet’s survival”. Strong words from this liberal pro-business, pro-GMO, yet also ‘green’ president, who is set on making his country the continent's first to enjoy 100% renewable electricity by 2030. President Ruto is voluntarily alarmist because, like many African leaders, he is tired of empty promises from rich countries and international finance institutions.

Almost ten years ago, at COP 21 in Paris in December 2015, the 195 participating countries made a commitment to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions to limit global warming to 1.5°C. However, scientific data shows that humanity is unlikely to meet this target. UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres even referred to an ‘era of global boiling’. We take stock of current and future problems, what solutions are needed, and how to get there.

Africa warming faster than the rest of the world

Despite accounting for just a fraction of global greenhouse gas emissions, Africa is bearing the brunt of the impact, with warming of 1.4°C compared with a global average of 1.1°C.

‘The success achieved this decade in reducing greenhouse gas emissions will determine whether global temperature rise can be limited to 1.5°C or whether it will rise to 2°C,’ writes the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) in its latest report. ‘The stakes could not be higher’, it warns: ‘The ramifications of each fraction of these degrees should not be underestimated, particularly for the most vulnerable populations.’ Compared with the pre-industrial era, the world has already warmed by 1.1°C. For United Nations Secretary General Antonio Guterres, “We are living through climate collapse in real time”, and we have entered “the era of global boiling”. The bad news for Africa is that it is warming even faster than the rest of the world (+1.4°C since the pre-industrial era). The IPCC's sixth report, published in the spring of 2023, estimates that climate change has already tipped the continent into a transition towards a ‘moderate’ level of risk, in terms of mortality, biodiversity, infectious diseases and agricultural productivity... The injustice is all the greater given that, as a barely industrialised continent, it contributes very little to global emissions! According to Antonio Guterres, “Africa has been the victim of the structural injustices of our international relations.”

Heading for 150 days of extreme heat a year

The poorest are the hardest hit. In a worst-case scenario of +4°C warming, West Africa would become unliveable.

The heatwave that hit West Africa between February and May, from Mauritania and Senegal to Benin and Nigeria, was exacerbated by global warming, according to climate experts working for the World Weather Attribution (WWA). Admittedly, this is the hot season, but it started as early as February on the coast, with abnormally high temperatures of over 45°C. In Kayes, in western Mali, the temperature reached 48.5°C on 3 April, exceeding the previous record of 48.3°C set in 2003 in Karima, Sudan. "This heatwave would not have occurred without climate change", concludes the WWA. The International Labour Organisation estimates that by 2030, productivity in West Africa will have fallen to -7% as a result of the heat making it physically impossible to work outdoors during the hottest times of the day.

‘The persistence of night-time temperatures in excess of 30°C prevents people from recovering, leading to a real danger to their health’, particularly for the poorest people, who live without air conditioning, under corrugated iron roofs, where the temperature is even higher than outside. According to the WWA, in a 2°C global warming scenario, the frequency of these heatwaves will increase tenfold. The IPCC reports that West Africa currently experiences around 50 days of extreme heat per year. In the least pessimistic scenario of +1.5°C warming, there will be up to 150 heatwave days a year. If the temperature rises by +2.5°C, there will be up to 250 days. And even 350 days in the cataclysmic scenario of +4.4°C warming: in other words, the sub-region would become uninhabitable...

More frequent and deadlier droughts

In North Africa, droughts could double in duration, from two to four months.

The drought that hit the Horn between 2020 and 2023 was the worst seen in four decades. A catastrophic succession of five poor rainy seasons killed millions of livestock, wiped out harvests and put the lives of 22 million people at risk, from Eritrea to Kenya. ‘This historic drought is the result of an unprecedented combination of a lack of rain and high temperatures, which could not have occurred without the consequences of human emissions of greenhouse gases,’ analyses the WWA. ‘Climate change has made agricultural drought in the Horn a hundred times more likely. It has had little effect on annual rainfall, but has strongly influenced the rise in temperatures’, which is responsible for the drying out of soils and plants.

‘If there had been no global warming since the pre-industrial era, this drought would have been much less severe.’ Rainy seasons become drier, and a low rainfall event is twice as likely. Now, ‘the exceptional drought in the Horn has a 5% chance of recurring every year’. According to Oxfam, 20 million people are threatened by hunger in southern Africa, which experienced its hottest February in a century. The IPCC's numerical models of climate change predict lower rainfall in the south-west of the continent (Angola, Namibia and South Africa) and along the coast of North Africa, where the drought could extend from two to four months, but increased rainfall in the eastern part of the continent.

Torrential rains on scorched, parched soil

There is still uncertainty as to the link between the El Niño phenomenon and climate change, but their effects are cumulative, particularly in the eastern half of the continent.

Catastrophic floods have followed drought in East Africa, particularly in Kenya, Tanzania and Burundi, causing hundreds of deaths and disappearances, and hundreds of thousands of refugees. The cause is the El Niño phenomenon, a natural oscillation in the climate that appears every two to seven years off the coast of Peru, around Christmas ("El Niño" refers to Jesus, in Spanish): the warming of the surface waters of the Pacific causes a chain of effects across a large part of the globe, including torrential rain in East Africa and the Horn. While there is a great deal of scientific uncertainty about the role of climate change on El Niño, the effects of these phenomena are cumulative, to the detriment of populations: Kenya has been hit this year by one of the most violent El Niño episodes since 1950. What's more, its impact is being amplified this year in East Africa by a second meteorological anomaly, known as the Indian Ocean Dipole (when the water surface is higher than normal to the west of the Indian Ocean and lower to the east).

El Niño is expected to generate global overheating in the summer of 2024, and increase the risk of fires, the "megafires" that release CO2 emissions by burning millions of trees. By the end of the year, El Niño could be followed by La Niña, an inverse phenomenon that would lead to extreme drought.

The vulnerability of the Gulf of Guinea

From Abidjan to Lagos, West Africa's gigantic coastal conurbation is on the front line of climate change, with rising sea levels and subsiding soil.

The Gulf of Guinea coastline is where a gigantic conurbation stretching for a thousand kilometres is taking shape: from Abidjan to Lagos, via Cotonou, it will have a population of over 50 million within a decade. It could even become the world's largest megalopolis by the end of this century. However, the Gulf of Guinea is threatened by two concomitant phenomena, with cumulative effects: the first is the global rise in sea levels, a direct consequence of global warming. According to the IPCC, as a result of the thermal expansion of the oceans and the melting of glaciers on land, sea levels have risen by more than 20 cm in a century. Between 2006 and 2015, sea levels rose by 3.6 mm per year, twice as fast as between 1900 and 1990. The rise is set to continue, with +40 cm by 2050 and a further 30 to 100 cm by 2100. The second phenomenon, often overlooked and still poorly documented, is subsidence, i.e. the gradual subsidence of the land. In the Gulf of Guinea, coastal areas are not very high, and are made up of friable sediments that erode easily. According to the ENGULF international scientific programme, launched in 2022 to quantify the rise in water levels along the West African coastline, most of this rise is not due to the rise in sea level, but rather to the compaction of sediments as a result of the construction of heavy urban infrastructure (buildings, roads, etc.) and the extraction of fluids (water, oil, etc.). In an article published in The Conversation in September, ENGULF scientists Marie-Noëlle Woillez, Philip Winderhoud and Pietro Teatini write: ‘A large proportion of the coastal populations and activities in the area are located in zones with altitudes of less than 2 metres, which are particularly exposed to rising water levels’, in Abidjan (5.6 million inhabitants), Lagos (24 million), Cotonou (1.2 million) and Accra (5 million). The problem and the potential resulting cataclysmic risks of marine submersion are as yet underestimated. Restoring mangroves, which serve as natural dykes, biodiversity reserves and CO2 traps, is one of the solutions.

Financial promises fulfilled at last

The promise by developed countries to allocate $100 billion a year to the energy transition in developing countries is finally materializing. The divergent priorities of the rich countries and the global financial architecture aren't conducive to funding.

According to the World Bank, ‘the cost of natural disasters has doubled in the poorest countries over the past decade’. In Africa, economic losses caused by climate-related disasters account for an average of 1.3% of GDP per year, four times more than in other emerging economies. The United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) estimates that African countries are already spending between 5% and 15% of their GDP on combating the impacts of climate change. On 29 May, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, the “club” of industrialised countries) announced that the promise made by developed countries in Copenhagen in 2009 to contribute $100 billion a year to the energy transition in developing countries had for the first time been kept and even exceeded, with $116 billion contributed in 2022. A new, more ambitious financing target will be negotiated at COP 29, to be held in Baku (Azerbaijan) in November. Ghanaian President Nana Akufo-Addo, whose country has defaulted on its debts, said at the recent Davos Forum that “the main challenge to achieving the development goals remains the ability to mobilise financial resources”, given the “limited fiscal resources” of African states, due to the predominance of informality in the economy.

At the Africa Climate Summit hosted by Kenyan President William Ruto in Nairobi last September, African countries called for a global tax on greenhouse gas emissions, ideally complemented by a financial transaction tax, as well as debt service relief. At a time when southern Africa is suffering from drought, Zambia, which has defaulted on its debt, lacks the resources to cope. Designed eighty years ago by Western countries, the global financial architecture, comprising the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, is “outdated, dysfunctional and unfair”, according to UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres.

Putting investors' minds at rest

The reluctance of private investors, who greatly overestimate the risks of investing in the continent, is hindering the energy transition's much-needed take-off.

Only 14% of international energy investment in Africa comes from the private sector, which is the lowest rate in the world, according to the AfDB. Yet the AfDB estimates that $200 billion a year in investment is needed if the continent is to achieve universal access to electricity and meet the targets set out in the December 2015 Paris Agreement. Africa's overall investment needs are estimated by UNECA at $1,700 billion a year. However, according to UNCTAD, not only is investment inadequate, it is actually falling: $600 billion in 2021, $544 in 2022... At COP 28, the United Arab Emirates announced the creation of a giant $30 billion private fund, called Alterra, to encourage and facilitate investment in the countries of the South, which are too often perceived as carrying greater risks, due to problems of governance, corruption and political unrest... A risk that is largely overestimated, as a study by the American firm Moody's Analytics showed in 2020: Africa's default rate is in fact only 2.1% (compared with 10% in Eastern Europe)! The AfDB, which allocates 40% of its projects to climate financing, is developing mitigation instruments to boost investor confidence. The AfDB is also banking on the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) to create regional synergies, such as the cross-border electric battery factory project between the DRC and Zambia, which will require USD 30 billion of investment.

Untapped potential of renewable energy

Solar energy, wind power, hydroelectricity, geothermal energy, essential minerals for batteries... Africa has all the natural resources it needs to ensure its energy transition and that of the world as a whole.

“Renewables are critical to achieving a successful energy transition and are a powerful catalyst for mitigating climate change,” says Francesco La Camera, Director General of the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), an intergovernmental organisation based in Abu Dhabi. Admittedly, the energy transition is underway, and humanity is moving towards a low-carbon economy. However, it is so behind schedule, that it is suicidally reckless: the shift could, and should, have been made as long ago as the late 1980s... However, IRENA believes that “the year 2022” was the real “turning point in the deployment of renewable energies”: for the first time, the imperative need for energy transition, which has finally taken hold in most minds, and the constraints of the war in Ukraine, which has forcibly weaned Westerners off their dependence on Russian gas, have tipped the costs of renewable energies, which are now “more competitive than fossil fuels”, IRENA points out. “In non-OECD countries, the savings made over the lifetime of the new capacity deployed in 2022 will reduce costs by $580 billion over the coming decades”, the agency calculates.

And yet, of the 473 GW of renewable energy capacity installed in 2023, only 4.6% is in Africa! The continent's potential remains largely under-exploited. With 3,000 hours of sunshine a year (four times more than in northern Europe), the continent has 40% of the world's available solar energy. But only 1% is currently being used. According to the African Solar Industry Association (AFSIA), the continent has around 16 GW of solar power, of which 3.7 GW was installed in 2023 - a figure that does not take into account private installations, which are difficult to record. South Africa, for example, has almost doubled its installations in the space of a year, with businesses and private individuals equipping themselves to cope with repeated power cuts by the national electricity company Eskom. This under-exploitation of renewable energy can also be seen in hydroelectricity (11% of Africa's 340 GW is harnessed) and wind power (0.2% of the estimated 33,000 GW potential). In the case of wind power, three quarters of new installations in 2023 are in China, the USA, Brazil and Germany.

Although it now accounts for 15% of Senegal's energy mix and 17% of Kenya's, the installation of new wind turbines is still well below expectations: “the construction of new wind turbines is costly and involves high levels of investment”, acknowledges the Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC) in its latest report, which identifies 140 projects underway on the continent, totalling 86 GW. It also deplores investor aversion: “Emerging countries face a higher cost of capital and pay higher interest rates.” Another renewable energy that is often overlooked is geothermal energy, i.e. the conversion of underground heat into electricity. Even though geothermal capacity on the continent has increased fivefold in ten years, reaching almost 1,000 MW, this energy remains largely untapped. In Africa, 21 countries possess this resource, according to the International Geothermal Association (IGA). A clean and virtually inexhaustible source of energy, it supplies almost half of Kenya's electricity, and could make the country the first in Africa to achieve 100% renewable electricity by 2030. However, according to the IGA, neighbouring Ethiopia, which relies more heavily on hydroelectricity (at the risk of falling out with Egypt), has geothermal potential equivalent to that of Kenya! The Nairobi Declaration calls for 300 GW of renewable electricity to be installed each year between now and 2030, while 600 million people (43% of the population) still have no access to electricity in sub-Saharan Africa. IRENA deplores the fact that “every year, the gap between what is needed and what has been achieved grows wider”. Even though “a virtuous circle of technologies, policies and innovations has enabled us to come a long way”, the scale of the task ahead keeps humanity “far from the 1.5°C target, which requires CO2 emissions to be cut by 37 gigatonnes and zero emissions to be achieved by 2050”. The deployment of renewable energies remains concentrated in the West and Asia: “Deep-rooted barriers stemming from the system and structures created by the fossil fuel era continue to hinder the progress of renewable energies”, concludes IRENA.

Yet demand for oil continues to rise

At COP 28, it was agreed that fossil fuels should be phased out gradually, as oil-producing countries consider them essential to their development and the financing of their energy transition.

According to the S&P Global Commodity Insights' report ‘Africa Energy and Economy: 2023 Review and 2024 Outlook’, oil production on the continent fell from 8 million barrels per day in 2019 to 6.5 million barrels per day in 2024. Nevertheless, consumption of CO2-emitting fuels will continue to grow, notes the same report. Because, while demand for fuels is declining in North America, Europe and Asia due to the boom in the electric car market, the cost of these new vehicles, the lack of infrastructure for recharging them and the absence of subsidies, means that the market is still in its infancy in sub-Saharan Africa. Which is absurd given that the continent is the source of most of the minerals needed for their batteries (cobalt, lithium, manganese, etc.). According to S&P “Africa's transport system will remain dependent on petrol and diesel in the medium term. Economic and demographic growth are even expected to increase demand for oil by 50% by 2050, from 3.3 million to 5 million barrels per day.” Exxon has announced that it will invest $15 billion in Angola, while Total Energies and Shell have announced investments of $6 billion and $5 billion respectively in Nigeria. IRENA is concerned that public policies are not all going in the right direction, pointing to the fuel subsidies introduced in 2022 to reduce inflation caused by the war in Ukraine. There is one piece of good news, however: in May, a fleet of 121 electric buses serving Greater Dakar was commissioned, capable of carrying 300,000 passengers a day. In any case, Africa's oil-producing states have no intention of bringing oil production to an abrupt halt. In Uganda and Tanzania, the recent Kingfisher and Tilenga oil and gas projects by France's TotalEnergies and China's CNOOC are being challenged in court by environmentalists, who see them as harmful and obsolete. However, the governments of Uganda and Tanzania see these investments as essential to their development. An argument supported at COP 28 by its President, Sultan Ahmed al-Jaber, CEO of the Emirati oil company ADNOC: the 195 participating states agreed to make the transition away from fossil fuels in a ‘fair, orderly and equitable manner’, without losing sight of the goal of carbon neutrality by 2050. John Kerry, the US special envoy, called it a ‘compromise’, while Antonio Guterres described the agreement as delaying the end of fossil fuels. “We are all in favour of clean energy, but it must be gradual and based on the needs of individual countries”, said Moussa Faki Mahamat, President of the African Union (AU) Commission, at COP 28.

Ali Ssekatawa, a director of the Petroleum Authority of Uganda (PAU), announced ‘a plan to use oil revenues to finance a twenty-fold increase in renewable energy in East Africa’. Ssekatawa criticises the ‘global North’, historically responsible for the dramatic situation facing humanity, for demanding that the South give up fossil fuels, while discreetly continuing its oil drilling activities, as the United Kingdom is doing in the North Sea to ensure its energy security to counter oil shortages because of Russia. The advocates of a smooth transition are arguing for the development of technologies to reduce CO2 emissions, carbon capture and carbon credits: at COP 28, under the impetus of al-Jaber, 50 oil and gas groups representing 40% of global production committed themselves to the decarbonisation of their extraction and production activities by 2050.

Environmentalists dismiss this as greenwashing, pointing out that the oil industry, which has been aware of its responsibility for global warming since the 1970s, emits most of its CO2 not during extraction, but during the combustion of its products ( factories, exhaust pipes, etc.).

Proliferation of nuclear power projects

Renewed interest across the continent in energy that emits no CO2 and is cleaning up its image, tarnished by Chernobyl and Fukushima. Initial investments are hefty, but Moscow says it is prepared to lend.

In Africa, as elsewhere, climate change is changing perceptions of nuclear power, as its reactors emit nothing but water vapour. Given that preventing climate change is not yet possible and that efforts are focused on urgently minimising its impacts, some ten African countries are taking a close interest in nuclear energy, especially as the probability of incidents leading to a disaster on the scale of Fukushima (Japan, March 2011) or Chernobyl (USSR, April 1986) is minimal. South Africa, struggling to free itself from its polluting and obsolete coal-fired power stations, is expanding its Koeberg nuclear power station which was commissioned in 1984 north of Cape Town and remains the only one in operation on the continent. In Egypt, the El-Dabaa power station to the west of Alexandria, built by the Russian state-owned operator Rosatom, is due to start producing electricity in 2026. In January, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sissi and Russian President Vladimir Putin launched work on this plant's fourth unit. According to al-Sissi, El-Dabaa will provide the continent's third most populous country with “clean, cheap and sustainable energy, which will reduce our dependence on fossil fuels”.

Russia, which lent Egypt $25 billion at 3% interest for the project, is the main contractor and will build the plant, supply the fuel, train the staff and provide maintenance. Mali and Burkina Faso, two countries close to the Kremlin, signed partnerships with Rosatom in Moscow last October. In 2022 Ghana, which intends becoming ‘Africa’s civil nuclear hub’ in the long term, signed an agreement with Japan and the United States for the construction of small modular reactors (SMRs) which require less water and uranium. Rwanda has signed an agreement with a German-Canadian start-up, Dual Fluid, to set up an experimental reactor. Morocco, Uganda and Kenya are also interested in atomic energy, and have contacted the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA, Vienna). However, given the extreme sensitivity of these cutting-edge technologies, it takes ten to fifteen years from the time a power plant project is launched to the time it becomes a reality.

Restoring and protecting the living world

Ending monoculture, a colonial import, and deforestation, reforesting and clean cooking: this is what it will take to protect Africa's environment in the face of climate change.

According to the FAO, 95% of African farmland depends on rainfall for irrigation. The climate emergency and the succession of droughts and floods it is causing mean that rapid, practical solutions need to be put in place. The colossal Great Green Wall (GGW) project, launched in 2007, and which is undoubtedly too complex to implement because of its sheer size, has been a disappointment. Only 15% of the planned 15km-wide barrier spanning eleven Sahelian countries, from Dakar to Djibouti, has been built in fifteen years, primarily in Senegal and Ethiopia. Nevertheless, there are a growing number of successful national and local initiatives. In Côte d'Ivoire, which has lost 80% of its forest cover since independence, the Abidjan Initiative, launched in 2022 by President Alassane Ouattara, aims to halt deforestation and restore 20% of degraded forests by 2030, while promoting a solution that is both simple and traditional: agroforestry.

Monoculture, unheard of in Africa before the end of the 19th century, is a colonial import. It depletes the soil and, during floods, exacerbates the impact of climate change, washing away the fields because there is nothing to anchor the soil, while also being highly susceptible to plagues of insects. Agroforestry, where trees provide shade for cocoa and coffee trees,increases yields, enriches the soil and creates symbioses between species. Other options suggested by African agronomists to combat climate change include the return to indigenous crops (such as sweet potatoes and Ethiopian teff), which require less water than imported crops such as wheat and maize, developing legumes (groundnuts, cowpeas, beans, etc.), which capture nitrogen from the air and trap it in the soil thereby encouraging the growth of neighbouring plants, and crop rotation.

Another major challenge is to stop gathering wood and burning charcoal, which is still the main cause of deforestation on the continent. Around 80% of sub-Saharan households use wood and charcoal for cooking, consuming between 0.4 and 1.5 kg of wood per person per day. This cooking method not only accelerates deforestation, but also pollutes homes with carbon emissions, leading to at least half a million premature deaths every year, most of them women suffering from lung disease.

Companies and start-ups across the continent are gearing up to supply households, particularly those in rural areas, with biogas (produced by fermenting organic waste) and solar cookers. However, these initiatives need support: according to the International Energy Agency (IEA), which organised a summit on the subject in Paris on 14 May, of the $4 billion needed, $2.2 billion has already been pledged. The widespread use of clean cooking on the continent by 2030 would enable the equivalent of a year's worth of greenhouse gas emissions from air and sea transport to be removed from the world's atmosphere!