Abidjan,

the Afro global city

Côte d’Ivoire’s economic capital and the planet’s third-largest French-speaking city is a never-ending work in progress, striving trying to correct the past while already thinking of the future, an urban planning challenge. A melting pot of cultures and peoples determined to forge a life in this megalopolis open to the wide world.

Here it is, sprawling, organized and somewhat chaotic at the same time, set between ocean and lagoon, already populated by nearly 6.5 million inhabitants. Growing exponentially, pulsating constantly, undergoing perpetual construction. The past few weeks have been particularly busy in this respect. A new exhibition park, the only one of its kind in francophone Africa, opened near the airport on July 17. Architect Pierre Fakhoury designed the bold-looking, contemporary complex as a modular structure to host everything from world-class sporting events to concerts, fairs and exhibitions. In early August, the ribbon was cut on the city’s fifth bridge, which connects the Plateau and Cocody districts. The cable-stayed span soaring above the lagoon has already become a defining landmark, a bit like Sydney’s Harbour Bridge and the Brooklyn Bridge in New York. And few weeks from now, cars will start crossing the fourth bridge, between Yopougon and Adjamé. Meanwhile, work on the Akwaba interchange between the airport and Port-Bouët has begun, bringing even more misery to motorists already at their wit’s end dealing with the city's constant and dreaded traffic jams. They will definitely heave a collective sigh of relief when the long tunnel under the Abobo round-about opens soon on the other side of Abidjan. And when the nearly two-billion-euro metro project will be reality. This is a highly complex human and technological challenge that has been under way for several years. The first line, which will speed passengers nearly 37 kilometers underground in a north-south direction between Anyama and Port-Bouët, is set to be up and running in 2027 or perhaps slightly later: The project is so politically sensible that information and pictures are hard to come by. In any case, it will have a major transformative, revolutionary impact. A whole new city life with shops, homes and leisure activities is already being planned along the route.

This overhaul involves the Cup of African Nations, which will take place from January 13 to February 11, 2024. This continental football competition will put the city’s fluidity and organization to a real-life test. Abidjan will be at the heart of the event, serving as the base for most of the officials, VIPs and high-profile individuals from around the world, as well as associations, the Confederation of African Football and delegates from the almighty FIFA. Two venues will host the matches. One, the Alassane Ouattara Olympic Stadium in Ebimpé, built with China, was inaugurated in October 2020 and has been upgraded to meet international standards. The other, a few kilometers away in the heart of the Plateau, is the fully renovated “old” Félix Houphouët-Boigny Stadium, whose seating capacity has been boosted to 40,000.

“BABI” BOUNCES BACK

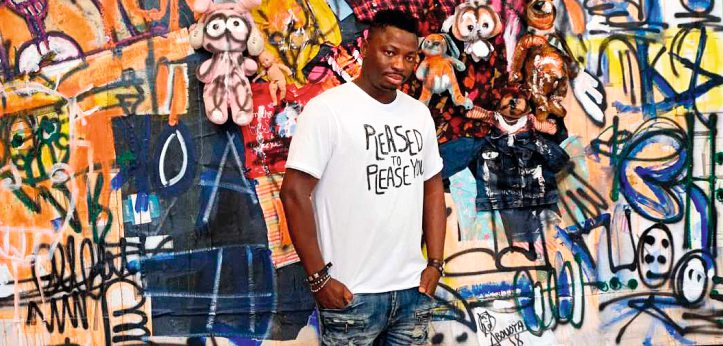

In short, the megalopolis is literally changing face, undergoing a metamorphosis. The arrival in power of Alassane Dramane Ouattara in 2011 and the years of brisk growth that followed would put tremendous energy into the engine of a wounded city. As if she was "on hold" since the late 1990s, with the famous Christmas coup d'état, the fall of Henri Konan Bédié and the years of paralysis that followed. And even more painfully, in the aftermath of the post-electoral crisis of November 2010. Abidjan was on its knees, bloodless. Traces of the violence of the fighting were literally on the walls. Water and electricity were in short supply, schools closed and public administrations devastated. Since then, the city has burst into a beehive of activity, with renovations and construction in full swing. Two bridges, as symbolic as they are concrete, have been built across the lagoon. Economic development and a yearly average growth rate of 8% have driven the city’s expansion and vibrancy despite the Covid-19 pandemic and the global macro-economic fallout from the war in Ukraine. Under the president’s leadership, the city is being rebuilt, renewed and reshaped. The country’s GDP has doubled since 2011 and looks set to reach nearly $100 billion by 2030. Abidjan is the epicenter and symbol of "the country’s economic second miracle". This is where it is happening. This is where the mighty and the humble, city dwellers and immigrants, seek their fortunes, create and invest. The African Development Bank (ADB) reopened its head office in Abidjan in September 2014, and the International Cocoa Organization (ICCO), established in London in 1973, moved there in April 2017. Planes and hotels are often fully booked with opportunity seeking investors. Meanwhile, creative trendsetters at the forefront of this nouvelle vague "Babi”, as Abidjan is affectionately called, meet up to roam from hipster bars to trendy restaurants, exhibitions and auction houses, while gallerists put their stamp on a fast-growing emerging market. At night, with the possible exception of the buttoned-down Plateau district, the city doesn’t sleep. In Zone 4 and Cocody, all cats are gray and the lights often stay on until dawn. Abidjan is a city with self assumed strong ambitions, with countless top restaurants and fine dining establishments offering dizzyingly high prices. Many of them are packed with young movers and shakers sporting the latest fashions from around the world and Africa.

Abidjan is the city of business, entrepreneurs, artists, intellectuals, partyers and adventurers drawn to all that glitters, a metropolis on the move, merging, creating and dreaming big. And then there is that special touch, an eagerness to embrace the outside world and others, with homes that welcome strangers, which is rare, after all. The people of Abidjan have no hang-ups, to say the least. The élites feel like citizens of the world. Steadily rising to prominence on the world stage, the bustling, radiant, vibrant city ranks among the few in Africa that can lay claim to global status. After all, Abidjan is the planet’s third-largest French-speaking city after Kinshasa and Paris.

Abidjan did not spring up out of nowhere. It began as a group of small villages clustering along the lagoon, Attié and Ebrié communities in the shadow of Grand-Bassam, the first colonial point of entry. In Bassam, the French built a picture-perfect town complete with post office, gendarmerie and school, a bit like they did in Saint-Louis in Senegal, to serve as a base for colonizing a wider area. But recurring yellow fever epidemics, especially in 1899, decimated the Europeans, putting an end to that ambition. Deciding to move to safer ground, they settled on the site of Abidjan (“land of the Bidjans”, an Ébrié sub-group), which had the necessary prerequisites to build a colonial city, provided a canal could be dug between the sea and the lagoon. In 1912, the commander of the “Cercle des Lagunes” was almost the last person to leave Bassam for Abidjan. The new capital prospered on the basis of racial segregation. The Plateau was the white, administrative district, Treichville the black, working-class neighborhood. A floating wooden bridge had to be built for laborers to get to work. Few traces of that period remain today. Abidjan has changed and grown along the amazing lagoon that gives the city its unique identity, as if seeking to erase its painful colonial past. As Houphouët-Boigny, the country’s first President, set about building a showcase that could rival the world other major urban centers, the Plateau and its first tall buildings came to symbolize the new, proud and independent Côte d’Ivoire. Houphouët-Boigny also harbored other ambitions, especially for his hometown, Yamoussoukro, which became the capital. The move was made for emotional reasons, and perhaps logical ones. But “the pearl of the savannahs” did not undermine “the pearl of the lagoons”. While Abidjan was no longer the political capital, it remained the throbbing center of the country and the melting pot of all its identities.

Like Yamoussoukro, Abidjan is an administratively and geographically autonomous district. Within its boundaries lie the 10 original communes Abobo, Adjamé, Attécoubé, Cocody, the Plateau, Yopougon, Treichville, Koumassi, Marcory and Port-Bouët and four adjoining sub- prefectures: Bingerville, Songon, Anyama and Brofodoumé. Each feels like a distinct city, with its own elected mayor, urban culture, identity and density. If Yopougon, population 1.5 million, were a separate metropolis, it would be the largest one in Côte d’Ivoire. Further north, Abobo trails just behind with 1.3 million inhabitants. “It’s a little like ECOWAS here, with all these nationalities living together,” its former mayor, the late Hamed Bakayoko, used to say. The Plateau is shifting into high gear. Cocody cultivates its trendiness, with yellow cabs on their last legs rattling down wide avenues. Marcory and Koumassi (people used to call them “the city beyond the bridges”) remain shopping hubs with vibrant night life. Nostalgic Treichville is seeking to restore its position as Abidjan’s biggest market. Meanwhile, rebellious Port Bouët is betting on the future with new developments near Félix Houphouët-Boigny Airport. In addition to these multiple identities, there are also about 30 Ébrié or Attié “villages”. While they have blended into the city, each one has held onto its traditions and informal courts. And no discussion of Abidjan would be complete without mentioning all the newcomers. Waves of migration from other parts of Côte d’Ivoire, Africa, France, Lebanon and Asia have shifted the makeup of the population and changed the face of the city, with each group adding its own complementary contributions to the mix. In Marcory’s high-end neighborhoods, buildings said to be financed by rich Malians looking for capital safety are springing up alongside the long-standing homes of wealthy Lebanese residents, while in Treichville, poor people from the sub-region sleep on the sidewalk around the market.

LOOKING FORWARD

Inequality is on starker display in Abidjan than anywhere else in the country. Some neighborhoods almost bring California or Portugal to mind with their upscale homes, tall, shady trees, luxurious concept buildings, malls and edgy shops. There are popular, populous sections that have become urban legends, such as Anoumabo, made famous by Magic System, and Blockhaus village around the majestic Hôtel Ivoire, which is still holding out against real estate speculators. But stains of poverty and ramshackle slums still account for one-fifth of the city, visually underscoring the urgent need for social policies and long-term urban renewal plans. Over a million people are exposed to hazardous conditions, especially flooding during the rainy season. The situation is so dire that rehabilitation is no longer an option. These neighborhoods will have probably to be torn down and rebuilt, a prospect that is not only costly but also politically explosive.

Finally, there is the question of sustainability. The entire city is built on a particularly fragile lagoon ecosystem. And pollution is multiplying: water treatment, rainwater management, industrial and urban waste, plastics, air quality, protection and enhancement of green spaces... There are many pressing issues. Plastics and industrial waste represent a particular and immediate danger. They are non-biodegradable, accumulate and threaten communities both rich and poor on the riverbanks. But the government’s awareness is also rising. The Akouédo landfill has been shut down and will be landscaped over to become an urban park, while infrastructure works aim to reduce traffic and its impact on air quality. There is increasing talk about clean energy. Electric vehicles are set to make up 30% of the total number of those on the city’s streets in the coming years. Lastly, Prime Minister Patrick Achi’s government, with backing from Morocco, is carrying out a major project to protect and improve Cocody Bay and the Ébrié Lagoon based on a comprehensive ecological-urban approach that includes the creation of water treatment plants, waste management facilities and a marina. The project is connected to the mouth of the Comoé River at Grand-Bassam to take pressure off the Ébrié Lagoon.

The other objective would be to deconcentrate economic activity. Abidjan carries a lot of weight, perhaps too much. The city accounts for 70-80% of the country's GDP. Development, jobs and activity must be shifted towards secondary cities and the hinterland. It is a daunting task. Responding to the urgences of today, correcting the pas, planing fort the future in a well alive city that cannot stop... In the words of Bruno Koné "today, we're more and more in anticipation mode, instead of being in catch-up mode." Abidjan, like all the world's major emerging metropolises, needs to think ahead. Understand its long-term dynamics. By 2030, 10 million people will be living in a conurbation stretching from Jacqueville (in the west) to Assinie (in the east). We'd even have to look even further ahead, into the next half-century. Between Abidjan and Lagos, one of the great "megalopolises" of the future is taking shape, with 1,200 kilometers of urban areas practically touching each other, passing through Ghana, Togo, Benin...

It could be dizzying. But "Babi" has faith. Here, between lagoon and ocean, in the shadow of towers and bridges, between scrubland and markets, between rich and poor, between yesterday and the avant-garde, one of the chapters of contemporary and future Africa is certainly being written.